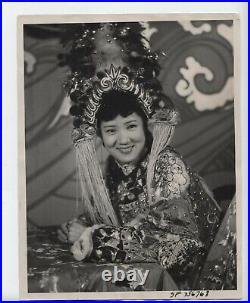

A VINTAGE ORIGINAL 7X9 INCH PHOTO FROM 1936 OF HEADWEAR IN CHINA IS ORNATE AND FORMAL AND MUCH BEJEWELED AND DECORATED. JOSEPHINE CHEW IS SHOWN WEARING ONE IN A SAN FRANCISCO CHINATOWN FASHION SHOW. The Chinatown centered on Grant Avenue and Stockton Street in San Francisco, California, (Chinese: ; pinyin: tángrénjie; Jyutping: tong4 jan4 gaai1) is the oldest Chinatown in North America and the largest Chinese enclave outside Asia. It is also the oldest and largest of the four notable Chinese enclaves within San Francisco. [3][4][5] Since its establishment in 1848, [6] it has been highly important and influential in the history and culture of ethnic Chinese immigrants in North America. There are two hospitals, several parks and squares, numerous churches, a post office, and other infrastructure. Recent immigrants, many of whom are elderly, opt to live in Chinatown because of the availability of affordable housing and their familiarity with the culture. [7] San Francisco’s Chinatown is also renowned as a major tourist attraction, drawing more visitors annually than the Golden Gate Bridge. Prostitution and ill repute. 1870s to the 1906 earthquake. 1906 to the 1960s. The Second World War Years and Immigration reform. Chinatown Community Development Center. Selected locations in Chinatown, San Francisco. Points of interest Parks and open spaces Hospital. 2 Saint Mary’s Square. 3 Sing Chong and Sing Fat buildings. 4 Nam Kue School. 7 Tin How Temple. 8 Ross Alley / Fortune Cookie factory. 10 Chinese Historical Society of America. Washington Street in Chinatown with Transamerica Pyramid in the background. Officially, Chinatown is located in downtown San Francisco, covers 24 square blocks, [9] and overlaps five postal ZIP codes (94108, 94133, 94111, 94102, and 94109). It is within an area of roughly 1? 2 mi (0.80 km) long (north to south) by 1? 4 mi (0.40 km) wide (east to west) with the current boundaries being, approximately, Kearny Street in the east, Broadway in the north, Powell in the west, and Bush Street in the south. Within Chinatown there are two major north-south thoroughfares. One is Grant Avenue , with the Dragon Gate (“Chinatown Gate” on some maps) at the intersection of Bush Street and Grant Avenue, designed by landscape architects Melvin Lee and Joseph Yee and architect Clayton Lee; Saint Mary’s Square with a statue of Dr. Sun Yat-Sen by Benjamin Bufano;[9] a war memorial to Chinese war veterans; and stores, restaurants and mini-malls that cater mainly to tourists. The other, Stockton Street , is frequented less often by tourists, and it presents an authentic Chinese look and feel reminiscent of Hong Kong, with its produce and fish markets, stores, and restaurants. It is dominated by mixed-use buildings that are three to four stories high, with shops on the ground floor and residential apartments upstairs. A major focal point in Chinatown is Portsmouth Square. [9] Since it is one of the few open spaces in Chinatown and sits above a large underground parking lot, Portsmouth Square bustles with activity such as T’ai Chi and old men playing Chinese chess. [9] A replica of the Goddess of Democracy used in the Tiananmen Square protest was built in 1999 by Thomas Marsh and stands in the square. It is made of bronze and weighs approximately 600 lb (270 kg). According to the San Francisco Planning Department, Chinatown is “the most densely populated urban area west of Manhattan”, with 34,557 residents living in 20 square blocks. [12] In the 1970s, the population density in Chinatown was seven times the San Francisco average. The median age was 50 years, the oldest of any neighborhood. [14] As of 2015, two thirds of the residents lived in one of Chinatown’s 105 single room occupancy hotels (SRO), 96 of which had private owners and nine were owned by nonprofits. [15] There are two public housing projects in Chinatown, Ping Yuen and North Ping Yuen. Most residents are monolingual speakers of Mandarin or Cantonese;[14] in 2015, only 14% of households in the SROs were headed by a person that spoke English fluently. [15] The areas of Stockton and Washington Streets and Jackson and Kearny Streets in Chinatown are almost entirely Chinese or Asian, with blocks ranging from 93% to 100% Asian. Many of those Chinese immigrants who gain some wealth while living in Chinatown leave it for the Richmond District, the Sunset District or the suburbs. Grant Avenue during Chinese New Year. Working-class Hong Kong Chinese immigrants began arriving in large numbers in the 1960s. Despite their status and professional qualifications in Hong Kong, many took low-paying employment in restaurants and garment factories in Chinatown because of limited English. An increase in Cantonese-speaking immigrants from Hong Kong and Mainland China has gradually led to the replacement in Chinatown of the Taishanese dialect by the standard Cantonese dialect. Due to such overcrowding and poverty, other Chinese areas have been established within the city of San Francisco proper, including one in its Richmond and three more in its Sunset districts, as well as a recently established one in the Visitacion Valley neighborhood. These outer neighborhoods have been settled largely by Chinese from Southeast Asia. There are also many suburban Chinese communities in the San Francisco Bay Area, especially in Silicon Valley, such as Cupertino, Fremont, and Milpitas, where Taiwanese Americans are dominant. Despite these developments, many continue to commute in from these outer neighborhoods and cities to shop in Chinatown, causing gridlock on roads and delays in public transit, especially on weekends. To address this problem, the local public transit agency, Muni, is planning to extend the city’s subway network to the neighborhood via the new Central Subway. Unlike in most Chinatowns in the United States, ethnic Chinese refugees from Vietnam have not established businesses in San Francisco’s Chinatown district, due to high property values and rents. Instead, many Chinese-Vietnamese – as opposed to ethnic Vietnamese who tended to congregate in larger numbers in San Jose – have established a separate Vietnamese enclave on Larkin Street in the heavily working-class Tenderloin district of San Francisco, where it is now known as the city’s “Little Saigon” and not as a “Chinatown” per so. Official Map of Chinatown (July 1885). Map is oriented with north to the right side. Dupont (now Grant) is the prominent street running north-south along the middle of the map. Full extent of map is Stockton (top/west), Kearny (bottom/east), California (left/south), and Broadway (right/north). Special attention is paid to vices: prostitution is marked in green (Chinese) and blue (white); joss houses are marked in red; opium dens are marked in bright yellow; and gambling is marked in pink. San Francisco’s Chinatown was the port of entry for early Chinese immigrants from the west side of the Pearl River Delta, speaking mainly Hoisanese[19] and Zhongshanese, [20] in the Guangdong province of southern China from the 1850s to the 1900s. [21] On August 28, 1850, at Portsmouth Square, [22]:9 San Francisco’s first mayor, John Geary, officially welcomed 300 “China Boys” to San Francisco. [23]:34-38 By 1854, the Alta California, a local newspaper which had previously taken a supportive stance on Chinese immigrants in San Francisco, began attacking them, writing after a recent influx that “if the city continues to fill up with these people, it will be ere long become necessary to make them subject of special legislation”. : literally “Tang people street”. These early immigrant settled near Portsmouth Square and around Dupont Street (now called Grant Ave). [23]:54-55 As the settlement grew in the early 1850s, Chinese shops opened on Sacramento St, which the Guangdong pioneers called “Tang people street” ;[24][22]:13 and the settlement became known as “Tang people town” , which in Cantonese is Tong Yun Fow. [22]:9-40 By the 1870s, the economic center of Chinatown moved from Sacramento St to Dupont St;[25]:15-16 e. In 1878, out of 423 Chinese firms in Chinatown, 121 were located on Dupont St, 60 on Sacramento St, 60 on Jackson St, and the remainder elsewhere. The area was the one geographical region deeded by the city government and private property owners which allowed Chinese persons to inherit and inhabit dwellings within the city. The majority of these Chinese shopkeepers, restaurant owners, and hired workers in San Francisco Chinatown were predominantly Hoisanese and male. [20] For example, in 1851, the reported Chinese population in California was about 12,000 men and less than ten women. [23]:41 Some of the early immigrants worked as mine workers or independent prospectors hoping to strike it rich during the 1849 Gold Rush. The west side of the Pearl River Delta of Guangdong, where most of the Chinese emigrated from, was subdivided into many distinct districts and some with distinct dialects. Several district associations, open to anyone emigrating from that district(s), were formed in the 1850s to act as a culture-shock absorber for newly arrived immigrants and to settle disputes among their member. Although there are some disagreement about which association formed first, by 1854, six of such district associations were formed, of various size and influence, and disputes between members of different associations became more frequent. Thus, in 1862, the six district associations (commonly called the Chinese Six Companies, even though the number of member associations varied through the years) banded together to resolve inter-district disputes. This was made formal in 1882 and incorporated in 1901 as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (on Stockton Street) to look after the general interest of the Chinese people living in a hostile western world. Founded purportedly in 1852, the Tin How Temple (Queen of Heaven and Goddess of the Seven Seas) on Waverly Place is the oldest Chinese temple in the United States. The original building was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake, and it opened on the top floor of a four-story building at 125 Waverly Place in 1910. After closing in 1955, the temple reopened in 1975, due to a resurgence of interest from a new immigrant population following the 1965 immigration reform act. The Chinese Presbyterian Church on Stockton Street can trace its roots to October 1852, when Cantonese-speaking Rev. William Speer, a missionary in Canton, came to work with the Chinese immigrants in San Francisco. In November 1853 he organized the first Chinese mission in the United States, which provided much needed medical aid and conducted day and night schools that taught English to Chinese immigrants. He also published a Chinese/English newspaper, the Oriental, which staunchly defended the Chinese as anti-Chinese sentiment began to grow in the 1850s. [28] The original building was destroyed by the earthquake, and the present church building on 925 Stockton Street was built in 1907. Other Christian denominations followed, including the Methodist Church on Washington Street (founded 1870, rebuilt 1911) and the First Baptist Church (founded 1880, rebuilt 1908 on Waverly Place) as well as Catholic, Congregational, and Episcopal. The pattern these early missions followed was to first conduct English language classes and Sunday schools. In these decades, the only English classes available to Chinese immigrants were those offered by these Christian missions. Some added rescue homes e. From prostitution, and social services for the sick and protection from racial discrimination. In these ways, the early Christian missions and churches in Chinatown gained widespread respect and new converts. The Street of the Gamblers (Ross Alley), Arnold Genthe, 1898. The population of Chinatown was predominantly male because U. Policies at the time made it difficult for Chinese women to enter the country. In the 1850s, San Francisco “was all but submerged in Caucasian forms of gambling and prostitution and lewdness”. [23]:57 During the late period of the California Gold Rush, a few Chinese female prostitutes began their sexual businesses in Chinatown. In addition, the major prostitution enterprises had been raised by criminal gang group “Tong”, importing unmarried Chinese women to San Francisco. [29] During the 1870s to 1880s, the population of Chinese sex workers in Chinatown grew rapidly to more than 1,800, accounting for 70% of the total Chinese female population. In the mid-19th century, police harassment reshaped the urban geography and the social life of Chinese prostitutes. Consequently, hundreds of Chinese prostitutes were expelled to side streets and alleys hidden from public traffic. [30] From 1870 to 1874, the California legislature formally criminalized the immigrant Asian women who were transported into California. In 1875, the U. Congress followed California’s action and passed the Page Law, which was the first major legal restriction to prohibit the immigration of Chinese, Japanese, and Mongolian women into America. [31] In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act declared that no more skilled or unskilled immigrants would be allowed to enter the country, which meant that many Chinese and Chinese Americans could not have families in America, because their wives and children were prohibited to immigrate. [32] Simultaneously, the public discourse began to accuse Chinese prostitutes of transmitting venereal diseases. Hugh Huger Toland, a member of the San Francisco Board of Health, reported that white boys and men contracted diseases when they visited “Chinese houses of prostitution” in Chinatown, in order to warn white citizens to stay away; Toland asserted that nine-tenths of his patients had patronized Chinese prostitutes. When these persons come to me I ask them where they got the disease, and they generally tell me that they have been with Chinawomen. [33]:12-13 [34]:27. All great cities have their slums and localities where filth, disease, crime and misery abound; but in the very best aspect which “Chinatown” can be made to present, it must stand apart, conspicuous and beyond them all in the extreme degree of all these horrible attributes, the rankest outgrowth of human degradation that can be found upon this continent. Here it may truly be said that human beings exist under conditions (as regards their mode of life and the air they breathe) scarcely one degree above those under which the rats of our water-front and other vermin live, breathe and have their being. And this order of things seems inseparable from the very nature of the race, and probably must be accepted and borne with-must be endured, if it cannot be cured-restricted and looked after, so far as possible, with unceasing vigilance, so that, whatever of benefit, “of degree, ” even, that may be derived from such modification of the evil of their presence among us, may at least be attained, not daring to hope that there can be any radical remedy for the great, overshadowing evil which Chinese immigration has inflicted upon this people. The Report of the Special Committee of the Board of Supervisors of San Francisco, on the Condition of the Chinese Quarter of that City (1885)[33]:5. By the end of the 19th century, Chinatown’s assumed reputation as a place of vice caused it to become a tourist destination, attracting numerous working class white people, who sought the oriental mystery of Chinese culture, and sought to fulfill their expectations and fantasies about the filth and depravity. The white customers’ patronization of Chinatown prostitutes was more extensive than gambling. After catering for three decades to white people as well as Chinese bachelors, Chinatown’s prostitution sector developed into a powerful vested interest, favoring the vice industry. [35] As the tourist industry grew up, the visitors came to include members of the white middle class, which pushed the vice businesses to transform into an entertainment industry as a more respectable form in which to serve white customers. Main article: Ah Toy. 1828 – 1928 was a Cantonese[36] prostitute and madam in San Francisco during the California Gold Rush, and purportedly the first Chinese prostitute in San Francisco. [37] Arriving from Hong Kong in 1849, [38] she quickly became the most well-known Asian woman in the Old West. [39] She reportedly was a tall, attractive woman with bound feet. [40] When Ah Toy left China for the United States, she originally traveled with her husband, who died during the voyage. Noticing the looks she drew from the men in her new town, she figured they would pay for a closer look. Her peep shows became quite successful, and she eventually became a high-priced prostitute. In 1850, Toy opened a chain of brothels at 34 and 36 Waverly Place[41] (then called Pike Street), importing girls from China as young as eleven years old to work in them. Her neighbors on Pike Street-conveniently linked to San Francisco’s business district by Commercial Street-included the elegant new “parlour house” of madame Belle Cora, and the cottage of Fanny Perrier, mistress of Judge Edward (Ned) McGowan. From 1868 until her death in 1928, she lived a quiet life in Santa Clara County, returning to public attention only upon dying three months short of her 100th birthday in San Jose. Officers of the Chinese Six Companies. The headquarters of the Chinese Six Companies on Stockton. Relations between the United States and Qing China were normalized through the Burlingame Treaty of 1868. Among other terms, the treaty promised the right of free immigration and travel within the United States for Chinese; business leaders saw China as a plentiful source of cheap labor, and celebrated the treaty’s ratification. [45] But this did not last for long. Fears began to arise among non-Chinese workers that they could be replaced, and resentment towards Chinese immigrants rose. [46] With extensive nationwide unemployment in the wake of the Panic of 1873, racial tensions in the city boiled over into full blown race riots. In response to the violence, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, also known as the Chinese Six Companies, which evolved out of the labor recruiting organizations for different areas of Guangdong, was created to provide the community with a unified voice. The heads of these companies advocated for the Chinese community to the wider business community as a whole and to the city government. The state legislature of California passed several measures to restrict the rights of Chinese immigrants, but these were largely superseded by the terms of the Burlingame Treaty of 1868. In 1880, the Burlingame Treaty was renegotiated and the United States ratified the Angell Treaty, which allowed federal restrictions on Chinese immigration and temporarily suspended the immigration of unskilled laborers. Anti-immigrant sentiment became federal law once the United States Government passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882: the first immigration restriction law aimed at a single ethnic group. This law, along with other immigration restriction laws such as the Geary Act, greatly reduced the numbers of Chinese allowed into the country and the city, and in theory limited Chinese immigration to single males only. Alternatively, prospective immigrants could become “paper sons” by purchasing the identity of Americans whose citizenship had been established by birthright. [27]:38-39 However, the Exclusion Act was credited with reducing the population of the neighborhood to an all-time low in the 1920s. Main immigration building on Angel Island. Many early Chinese immigrants to San Francisco and beyond were processed at Angel Island, in the San Francisco Bay, which is now a state park. Unlike Ellis Island on the east coast where prospective European immigrants might be held for up to a week, Angel Island typically detained Chinese immigrants for months while they were interrogated closely to validate their papers. The detention facility was renovated in 2005 and 2006 under a federal grant. As in much of San Francisco, a period of criminality existed during the late 19th century; many tongs arose, trafficking in smuggling, gambling and prostitution. From the mid-1870s, turf battles sprang up over competing criminal enterprises. By the early 1880s, the term Tong war was being popularly used to describe these periods of violence in Chinatown. At their height in the 1880s and 1890s, twenty to thirty tongs ran highly profitable gambling houses, brothels, opium dens, and slave trade enterprises in Chinatown. Overcrowding, segregation, graft, and the lack of governmental control contributed to conditions that sustained the criminal tongs until the early 1920s. Chinatown’s isolation and compact geography intensified the criminal behavior that terrorized the community for decades despite efforts by the Six Companies and police/city officials[47] to stem the tide. The San Francisco Police Department established its so-called Chinatown Squad in the 1880s, consisting of six patrolmen led by a sergeant. However, the Squad was ineffective largely by design. An investigation published in 1901 by the California state legislature found that Mayor James D. Phelan and Police Chief William P. Had knowingly tolerated gambling and prostitution in Chinatown in the interest of bolstering municipal revenue, calling the police department so apathetic in putting down the horrible system of slavery existing in Chinatown as to justify your committee in believing it criminally negligent. [48] Phelan and Sullivan testified it would take between 180 and 400 policemen to enforce the laws against gambling and prostitution, which was contradicted by the ex-Chief of Police William J. Biggy, who said 30 “earnestly directed” policemen would suffice. Chinatown, as it is at present, cannot be rendered sanitary except by total obliteration. It should be depopulated, its buildings leveled by fire and its tunnels and cellars laid bare. Its occupants should be colonized on some distant portion of the peninsula, where every building should be constructed under strict municipal regulation and where every violation of the sanitary laws could be at once detected. The day has passed when a progressive city like San Francisco should feel compelled to tolerate in its midst a foreign community, perpetuated in filth, for the curiosity of tourists, the cupidity of lawyers and the adoration of artists. Williamson, Annual Report to the Board of Health (quoted in 1901)[50]. In March 1900, a Chinese-born man who was a long-time resident of Chinatown was found dead of bubonic plague. The next morning, all of Chinatown was quarantined, with policemen preventing “Asiatics” (people of Asian heritage) from either entering or leaving. The San Francisco Board of Health began looking for more cases of plague and began burning personal property and sanitizing buildings, streets and sewers within Chinatown. Chinese Americans protested and the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association threatened lawsuits. The quarantine was lifted but the burning and fumigating continued. A federal court ruled that public health officials could not close off Chinatown without any proof that Chinese Americans were any more susceptible to plague than Anglo Americans. [51][52][53][54][55]. Looking east down Clay St at the Great Fire on 18 April 1906: Arnold Genthe. The Chinatown neighborhood was completely destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire that leveled most of the city. The fire had full sway, and Chinatown, for the removal of which many a scheme has been devised, is but a memory. Oakland Tribune, April, 1906. Plans to relocate Chinatown predated the earthquake several years. At the 1901 Chinese Exclusion Convention held in San Francisco, A. Sbarboro called Chinatown “synonymous with disease, dirt and unlawful deeds” that “give[s] us nothing but evil habits and noxious stenches”. With Chinatown completely demolished by the Great Fire, which ended on April 21, 1906, the City seized the chance to remove the Chinese from the old downtown business district. Certain city officials and real-estate developers made more formal plans to move Chinatown to the Hunters Point neighborhood at the southern edge of the city, [56] or even further south to Daly City. Abe Ruef, the political boss widely considered to be the power behind Mayor Eugene Schmitz, invited himself to become part of the Committee of Fifty and, within a week of the end of the Great Fire, on Saturday, April 27, 1906, [25]:61-63 formed an additional Subcommittee on Relocating the Chinese, because he felt the land was too valuable for Chinese. Opposition arose, however, from politicians who feared that the removal of the Chinese would affect San Francisco’s lucrative trade with Asian countries. Moreover, the government of China was also opposed, and soon after the earthquake, Tsi Chi Chow, the first secretary of the Chinese legation in Washington, DC, arrived in San Francisco, conveying to California governor George Pardee the opposition of China’s Empress Dowager Cixi to the plan. [57] The representatives, “acting unofficially”, stated the only way to remove the Chinese from the old Chinatown would be to give them a place elsewhere that would be acceptable for their purpose, when they might be willing to move. “[58] The San Francisco Call reported it as “a vigorous protest and noted that as the site of the Chinese consulate was the property of Imperial China, it could not be reassigned by the city. On May 10, 1906, the Subcommittee met with representatives from the Chinese community, the Chinese Six Companies, who said that they would either rebuild in their old Chinatown quarters or move across the bay to Oakland, where most of the Chinatown refugees had fled. [25]:65 Other community leaders pointed out that displaced residents may not stop to resettle in Hunters Point, moving further to other West Coast cities like Seattle or Los Angeles, taking the pool of cheap labor with them. [60] On July 8, 1906, after 25 committee meetings and considering various alternative sites in the City, the Subcommittee submitted a final report stating their inability to drive the Chinese from their old Chinatown quarters. [25]:66 Ironically, plans to relocate Chinatown failed in the end because restrictive housing covenants in other areas of the City prohibited Chinese from settling elsewhere. [61]:92 In any event, the ability to rebuild in their old Chinatown quarters was the first significant victory[62] for the Chinese community in Chinatown. Looking north along Grant from the intersection of Grant and Pine. The distinctive pagoda-topped roofs of the Sing Fat and Sing Chong buildings are on the left side of each picture. The dragon street lamp (right) was installed in 1925 for the San Francisco Diamond Jubilee Festival. Even when the Subcommittee was bringing its relocation attempt to an end, the Chinese were already rebuilding, albeit with temporary wooden buildings which did not required permits. By June 10, 1906, twelve Chinese businesses were opened in Chinatown, including a couple of cafes. The actual reconstruction did not begin until October 1, 1906, when the City granted 43 building permits to Chinese businesses. By the time of the first post-quake Chinese New Year in 1907, several dozen buildings were completed, using old bricks unburnt by the fire, and Chinatown was filled with happy people. The reconstruction of Chinatown was completed more or less in 1908, a year ahead of the rest of the City. A group of Chinese merchants, including Mendocino-born Look Tin Eli, hired American architects to design in a Chinese-motif “Oriental” style in order to promote tourism in the rebuilt Chinatown. [63] The results of this design strategy[64] were the pagoda-topped buildings of the Sing Chong and Sing Fat bazaars on the west corners of Grant Ave (then Dupont St) and California St, which have become icons of San Francisco Chinatown. In November 1907, an article extolling the virtues of the “new Chinatown of San Francisco” was written, praising the new substantial, modern, fireproof buildings of brick and stone… Following the Oriental style of architecture” and declaring “[n]o more picturesque squalor, no more gambling dens, opium joints or public haunts of vice would be tolerated, at the command of the Chinese Six Companies. When the earthquake destroyed Chinatown’s wooden tenements, it also dealt a blow to the tongs. Criminal tongs continued on until the 1920s, when legitimate Chinese merchants and a more capable Chinatown Squad under Sgt. Jack Manion gained the upper hand. Manion was appointed leader of the Squad in 1921 and served for two decades. Stiffer legislation against prostitution and drugs ended the tongs. [66] The Chinatown Squad was finally disbanded in August 1955 by Police Chief George Healey, upon the request of the influential Chinese World newspaper, which had editorialized the Squad was an “affront to Americans of Chinese descent”. While the Chinese merchants succeeded in rebuilding in a tourist-attractive way, they could not influence the landlords, most of which were not Chinese, to provide adequate housing for the Chinese residents. In a 1930 Community Chest Survey of 153 Chinatown families, 32 families, with an average of five persons each, lived in one room each; only 19 families had complete bath tub, kitchen, and toilet facilities; on the average, there was one kitchen for 3.1 families and one toilet for 4.6 families (or 28.3 persons). Crowded inadequate living conditions contributed to a high death rate for the Chinese. The Chinese were no longer a problem for the city; they were forgotten. Dragon Street Lamp on Grant Ave. The famous Sam Wo restaurant opened in 1912. Designed by W(alter) D’Arcy Ryan, who also designed the “Path of Gold” streetlights along Market Street, [27]:124-125 the distinctive 2,750 pounds (1,250 kg) street lamp, painted in traditional Chinese colors of red, gold and green, was composed of a cast-iron hexagonal base supporting a lotus and bamboo shaft surmounted with two cast-aluminum dragons below a pagoda lantern with bells and topped by a stylized hexagonal red roof[69]-all in keeping with the Oriental style pioneered by Look Tin Eli (1910). Since then, the original molds were used to add 24 more dragon street lamps were in 1996 (distinguishable by the foundry, whose name and location in Emporia, Kansas is cast on an access door at the base), and later, 23 more were added along Pacific by PG&E. Chinatown (facing north from just south of the corner of Grant and Commercial) in 1945. Prominently lit buildings on the left (west) side of Grant include the Ying On (closer to camera) and Soo Yuen (in background); the Eastern Bakery sign is lit on the right (east) side of Grant. During the Great Depression, many nightclubs and cocktail bars were started in Chinatown. [71] The Forbidden City nightclub, located at 369 Sutter Street in Chinatown and run by Charlie Low, became one of the most famous entertainment places in San Francisco. [72] While it was doing business, from the late 1930s to the late 1950s, the Forbidden City gained an international reputation with its unique showcase of exotic oriental performance from Chinese American performers. [73] Another popular club for tourists and LGBT clients was Li Po, which, like Forbidden City, combined western entertainment with “Oriental” culture. It was advertised in a 1939 tourism guide book as a “jovial and informal Chinatown cocktail lounge” where one could find “love, passion, and nighttime”. [16] As of 2018, it was still in operation at 916 Grant Avenue. For the Chinese in Chinatown, the war came upon them in September 1931, when Japan attacked the Manchurian city of Mukden, and became unignorable in July 1937, when Japan launched a major offensive southward from their base in Manchuria towards the heart of China. In response, the Chinese Six Companies convened many community organizations together, from which was founded the Chinese War Relief Association, to raise funds from the Chinatown communities through out the U. To aid civilians trapped by the war in China. As Chinese Americans became more visible in the public eye during the period leading to the U. Involvement in the war, the negative image of China and the Chinese began to erode. Scott Wong[74]:42. Once China became an ally to the U. In World War II, a positive image of the Chinese began to emerge. In October 1942, Earl Warren, running for Governor of California, wrote, Like all native born Californians, I have cherished during my entire life a warm and cordial feeling for the Chinese people. [74]:89 In her goodwill tour of the U. Starting in February 1943, Madame Chiang Kai Shek probably did more to change the American attitude towards the Chinese people than any other single person. [27]:53-54 She was hosted by the First Lady and President Franklin D. Roosevelt; she was the second woman and the first Chinese to address the U. The American public embraced her with respect and kindness, which is in stark contrast to the treatment of most Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans. [74]:89-109 To the Chinese in Chinatown, she became an icon of the war years. In December 1943, in recognition of the important role of China as an ally in the war, the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed by the Magnuson Act, which allowed for naturalization but restricted Chinese immigrants to a small annual quota of 105 new entry visas. The repeal of the Exclusion Act and other immigration restriction laws, in conjunction with passage of the War Brides Act in December 1945, allowed Chinese-American veterans to bring their families outside of national quotas and led to a major population boom in the area during the 1950s. However, tight quotas on new immigration from China still applied until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was passed. In the 1948 landmark case of Shelley v. Supreme Court ruled without dissent that enforcing racially restrictive covenants in property deeds violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and thus such covenants are unenforceable in court, which lifted the invisible walls around Chinatown, [68] permitting some Chinese Americans to move out of the Gilded Ghetto[77] into other neighborhoods of the City and gain a foothold on the middle class. Twenty years later, such racially restrictive covenants were outlawed in the 1968 Fair Housing Act. San Francisco artist Frank Wong created miniature dioramas that depict Chinatown during the 1930s and 1940s. [78] In 2004, Wong donated seven miniatures of scenes of Chinatown, titled “The Chinatown Miniatures Collection, ” to the Chinese Historical Society of America (CHSA). [79] The dioramas are on permanent display in CHSA’s Main Gallery. View north along Grant Avenue, approximately taken from the sidewalk in front of 645 Grant (1965). In the 1960s, the shifting of underutilized national immigration quotas brought in another huge wave of immigrants, mostly from Hong Kong. This changed San Francisco Chinatown from predominantly Hlay Yip Wah (Sze Yup or Hoisan Wah)-speaking to Sam Yup Wah (standard Cantonese)-speaking. During the same decade, many stores moved from Grant Avenue to Stockton Street, drawn by lower rents and the better transportation enabled by the 30-Stockton Muni trolleybus line. The Dragon Gate at Grant and Bush, now a prominent landmark, was dedicated in 1970. There were areas where many Chinese in Northern California living outside of San Francisco Chinatown could maintain small communities or individual businesses. Nonetheless, the historic rights of property owners to deed or sell their property to whomever they pleased was exercised enough to keep the Chinese community from spreading. However, in Shelley v. Kraemer, the Supreme Court had ruled it unconstitutional for property owners to exclude certain groups when deeding their rights. This ruling allowed the enlargement of Chinatown and an increase in the Chinese population of the city. At the same time, the declining white population of the city as a result of White Flight combined to change the demographics of the city. Neighborhoods that were once predominately white, such as Richmond District and Sunset District and in other suburbs across the San Francisco Bay Area became centers of new Chinese immigrant communities. This included new immigrant groups such as Mandarin-speaking immigrants from Taiwan who have tended to settle in suburban Millbrae, Cupertino, Milpitas, Mountain View, and even San Jose – avoiding San Francisco as well as Oakland entirely. Imperial Palace Restaurant in 2010. The Imperial Palace replaced the Golden Dragon in the same space at 816 Washington. With these changes came a weakening of the Tongs’ traditional grip on Chinese life. Newer Chinese groups often came from areas outside of the Tongs’ control, so the influence of the Tongs and criminal groups associated with them, such as the Triads, grew weaker in Chinatown and the Chinese community. [citation needed] However, the presence of the Asian gangs remained significant in the immigrant community, and in the summer of 1977, an ongoing rivalry between two street gangs, the Wah Ching and the Joe Boys, erupted in violence and bloodshed, culminating in a shooting spree at the Golden Dragon Restaurant on Washington Street. Five people were killed and eleven wounded, none of whom were gang members. The incident has become infamously known as the Golden Dragon massacre. Five perpetrators, who were members of the Joe Boys gang, were convicted of murder and assault charges and were sentenced to prison. [82] The Golden Dragon closed in January 2006 because of health violations, and later reopened as the Imperial Palace Restaurant. Other notorious acts of violence have taken place in Chinatown since 1977. On May 14, 1990, San Francisco residents who had just left The Purple Onion, a nightclub located where Chinatown borders on North Beach, were shot as they entered their cars. 35-year-old Michael Bit Chen Wu was killed and six others were injured, among them a critically wounded pregnant woman. [84] In June 1998, shots were fired at Chinese Playground, wounding six teenagers, three of them critically. A 16-year-old boy was arrested for the shooting, which was believed to be gang-related. [85] On February 27, 2006, Allen Leung was shot to death in his business on Jackson Street;[86] Raymond “Shrimp Boy” Chow, who succeeded Leung as head of the Ghee Kung Tong, was later convicted in 2016 of soliciting Leung’s murder as fallout from the corruption investigation of Leland Yee, [87] and Raymond “Skinny Ray” Lei was indicted for committing the murder in 2017. View north along Stockton from atop the north portal of the Stockton Street Tunnel in 2011. San Francisco’s Chinatown is home to the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (known as the Chinese Six Companies), which is the umbrella organization for local Chinese family and regional associations in Chinatown. It has spawned lodges in other Chinatowns in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including Chinatown, Los Angeles and Chinatown, Portland. The Chinese Culture Center is a community based non-profit organization located on the third floor of the Hilton San Francisco Financial District, across Kearny Street from Portsmouth Square. The Center promotes exhibitions about Chinese life in the United States and organizes tours of the area. The Chinese Historical Society of America is housed in a building designed by Julia Morgan as a YWCA, at 965 Clay. Southern entrance to Chinatown on Grant. One of the most photographed locations. San Francisco Dragon Gate to Chinatown. Saint Mary’s Square. Features statue of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, by Beniamino Bufano and a memorial for Chinese-American veterans of World Wars I and II. St Mary’s Square 03. Designed by Ross & Burgren and among the earliest buildings erected after the 1906 earthquake. Strong influence on Chinatown architecture. San Francisco – Chinatown & California Street Cable Car (1098847880). Sing Fat MG 7885bui (38545078252). Nam Kue Chinese School. Private school offering classes in Chinese culture, history, and language. Nam Kue Chinese School – San Francisco, CA – DSC02361. Oldest public space in San Francisco. All calls to Chinatown were routed by name and occupation until 1948. Oldest Taoist temple in Chinatown. Chinatown 23 Buddhist Temple (4253514495). Between Jackson, Washington, Grant, and Stockton. Often used as a backdrop for films. Chinatown San Francisco (4678554439). Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Company. Working fortune cookie factory and shop. 15 Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Factory. 1925 (demolished), 1977, 2017. Only Chinese-language hospital in United States. Chinese Historical Society of America. Former YWCA building designed by Julia Morgan. Sometimes called the “White House” of Chinatown. 1830 Painted Lady (31697805676). Dragon on Market, 2011. In the 1950s, [89]:71-73 during the Korean war, a number of Chinese-American leaders, led by W. Wong, [90] organized the San Francisco Chinese New Year Festival and Parade, [91] including art shows, street dances, martial arts, music, and a fashion show. The 1953 parade was led by Korean war veteran, Joe Wong, and featured the Miss Chinatown festival queen and the dragon. [91]:29 By 1958, the festival queen had been formally expanded into the pageant of Miss Chinatown U. [91]:56 In 1994, around 120 queer Asian Americans joined the annual parade, which was the first time that Asian American queer community had appeared in public and gained acceptance from Chinese-American society. San Francisco Chinatown’s annual Autumn Moon Festival celebrates seasonal change and the opportunity to give thanks to a bountiful summer harvest. The Moon Festival is popularly celebrated throughout China and surrounding countries each year, with local bazaars, entertainment, and mooncakes, a pastry filled with sweet bean paste and egg. The festival is held each year during mid-September, and is free to the public. Funeral procession in Chinatown along Grant with marching band, taken facing south near the corner of Grant and Jackson, 2016. Chinatown is frequently the venue of traditional Chinese funeral processions, where a marching band (playing Western songs such as Nearer, My God, to Thee) takes the street with a motorcycle escort. [93] The band is followed by a car displaying an image of the deceased (akin to the Chinese custom of parading a scroll with his or her name through the village), and the hearse and the mourners, who then usually travel to Colma south of San Francisco for the actual funeral. [94] By union regulation, the procession route starts at the Green Street Mortuary proceeding on Stockton Street for six blocks and back on Grant Avenue, taking about one hour. Chinatown Community Development Center is an organization formed in 1977 after the merger of the Chinatown Resource center and the Chinese Community Housing Corporation. [95] The organization was started by Gordon Chin, who served as Executive Director since 1977 until he was succeeded by the organization’s Deputy Director Rev. Norman Fong on October 1, 2011. The organization advocates and provides services to San Francisco’s Chinatown. They have also started many groups, Adopt-An-Alleyway Youth Empowerment Project being the most notable, [96] and have been involved with many tenant programs. In the citywide Board of Supervisors elections, Chinatown forms part of District Three and in 2014 accounted for 44% of both registered voters and ballots cast. [14] The two main newspapers read among residents are Sing Tao Daily and World Journal. SF Mayor Willie Brown attends a Chinese New Year Celebration in Chinatown (1999). San Francisco Chinatown restaurants are considered to be the birthplace of Americanized Chinese cuisine such as food items like Chop Suey while introducing and popularizing Dim Sum to American tastes, as its Dim Sum tea houses are a major tourist attraction. Johnny Kan was the proprietor of one of the first modern style Chinese restaurants, which opened in 1953. Many of the district’s restaurants have been featured in food television programs on Chinese cuisine such as Martin Yan’s Martin Yan – Quick & Easy. Chinatown has served as a backdrop for several movies, television shows, plays and documentaries including The Maltese Falcon, What’s Up, Doc? Big Trouble in Little China, The Pursuit of Happyness, The Presidio, Flower Drum Song, The Dead Pool, and Godzilla. Noted Chinese American writers grew up there such as Russell Leong. Contrary to popular belief, while the Chinese-American writer Amy Tan was inspired by Chinatown and its culture for the basis of her book The Joy Luck Club and the subsequent movie, she did not grow up in this area; she was born and grew up in Oakland. [98] Notable 1940s basketball player Willie “Woo Woo” Wong, who excelled in local schools, college and professional teams, was born in, and grew up playing basketball in, Chinatown; a local playground bears his name. Cable Car 56 ascends Nob Hill from Chinatown along California Street; prominent buildings shown include the Transamerica Pyramid, Sing Chong Bazaar, Hartford Building, and Old Saint Mary’s Cathedral. See also: List of streets and alleys in Chinatown, San Francisco. San Francisco cable cars have long served areas of Chinatown; the modern system serves the southern (along California Street) and western (along Powell Street) sections of the neighborhood. The Stockton Street Tunnel was completed in 1914 and brought San Francisco Municipal Railway Streetcar service to Stockton Street. After the tracks were removed, the overhead wires were maintained and buses replaced streetcars along the route. The 30 Stockton and 45 Union-Stockton are among the most heavily ridden lines in the system. [citation needed] Modern rail service will return at Chinatown station upon completion of the Central Subway. The Broadway Tunnel was completed in 1952 and was intended to serve as a connection between the Embarcadero Freeway and the Central Freeway. These plans did not materialize due to the highway revolts at the time. [citation needed] The tunnel currently serves to connect Chinatown with Russian Hill and Van Ness Avenue to the west. In the 1980s, Chinatown merchants were opposed to the removal of the Embarcadero Freeway, but these objections were overturned after it was damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. The 49-Mile Scenic Drive is routed through Chinatown, with particular attention paid to the corner of Grant and Clay. San Francisco Bay Area portal. 1877 San Francisco Riot. History of the Chinese Americans in San Francisco. Queer history in Chinatown, San Francisco. Recommended reading: Chinese in America, Immigration at the Golden Gate, and The Children of Chinatown. First Chinese immigrants – two men and one women – arrive in San Francisco on the American brig, Eagle. Gold discovered at Sutter’s Mill. Mary’s Church erected. Presbyterian Church in Chinatown is the first Asian church in North America. “The Chinese School” was created. Chinese children were assigned to this “Chinese only” school. They were not permitted into any other public schools in San Francisco. California passes a law against the importation of Chinese, Japanese, and “Mongolian” women for the purpose of prostitution. Anti-Chinese ordinances are passed in San Francisco to curtail their housing and employment options. Chinese Congregational Church and Chinese United Methodist Church are established. Presbyterian Mission Home for Chinese women, later renamed Donaldina Cameron House is established. Page Law bars Asian prostitutes, felons, and contract laborers. US and China sign treaty giving the US the right to limit but “not absolutely prohibit” Chinese immigration. California’s Civil Code passes anti-miscegination law. First Chinese Baptist Church founded. 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act bans immigration of Chinese laborers to the United States and prohitbits Chinese from becoming naturalized citizens. (Chinese Exclusion Act List). The “Chinese School” was renamed the” Oriental School, ” so that Chinese, Korean, and Japanese students could be assigned to the school. Cumerland Presbyterian Church is established. Tung Wah Dispensary opens in Chinatown. Chinese exclusion act extended for another 10 years. Chinese exclusion act made indefinite. Independent Baptist Church is established. San Francisco earthquake and fire. True Sunshine Episcopal is established. Chinese Chamber of Commerce formed. Angel Island Immigration Station opens and operates as a detention and processing center for Chinese immigration. Thousands of Chinese immigrants spend weeks and months detained, undergoing rigorous interrogations by U. Chinatown YMCA is established. Chinatown YWCA is established. Chinatown Public Library opens. The “Oriental School” was renamed Commodore Stockton School. Alice FongYu was the first Chinese teacher. Students were barred from speaking Chinese in school or on the playground. The Nam Kue School is built. Tung Wah Dispensary is relocated and renamed Chinese Hospital. The Chinese Playground is built. English-Language Newspaper for Chinatown. Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act by Congress and grants Chinese aliens naturaliztion rights. Displaced Person’s Act. Church of the Nazarene is established. First Chinese Southern Baptist Church is established. Immigration and Nationality Act. Chinese Historical Society of America founded. Luthern Church of the Holy Spirit is established. Immigration Act of 1965. First Miss Teen Chinatown Pageant. San Francisco Chinese Baptist Church is established. First Chinese American women seen regularly on national television. Chinese Grace Church is established. San Francisco Evangelical Free Church is established. Immigration Reform Act of 1995. Commodore Stockton Elementary School was renamed Gordon J. Lau Elementary School in honor of the late civic leader and advocate for the Chinese community. Mayor Edwin Lee elected as first Chinese American mayor in San Francisco’s history. Point Guard Jeremy Lin become the first Chinese American basketball player to start in the NBA. A Chinatown (Chinese: ; pinyin: Tángrénjie; Jyutping: tong4 jan4 gaai1) is an ethnic enclave of Chinese people located outside mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau or Taiwan, most often in an urban setting. Areas known as “Chinatown” exist throughout the world, including Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa, Australasia and the Middle East. The development of most Chinatowns typically resulted from mass migration to an area without any or with very few Chinese residents. Binondo in Manila, established in 1594, is recognized as the world’s oldest Chinatown. Notable early examples outside Asia include San Francisco’s Chinatown in the United States and Melbourne’s Chinatown in Australia, which were founded in the mid-19th century during the California gold rush and Victoria gold rush, respectively. A more modern example, in Montville, Connecticut, was caused by the displacement of Chinese workers in the Manhattan Chinatown following the September 11th attacks in 2001. 1970s to the present. Benevolent and business associations. Oxford Dictionaries defines “Chinatown” as… A district of any non-Asian town, especially a city or seaport, in which the population is predominantly of Chinese origin. [3] However, some Chinatowns may have little to do with China. [4] Some “Vietnamese” enclaves are in fact a city’s “second Chinatown”, and some Chinatowns are in fact pan-Asian, meaning they could also be counted as a Koreatown or Little India. [5] One example includes Asiatown in Cleveland, Ohio. It was initially referred to as a Chinatown but was subsequently renamed due to the influx of non-Chinese Asian Americans who opened businesses there. Today the district acts as a unifying factor for the Chinese, Taiwanese, Korean, Japanese, Filipino, Indian, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian, Nepalese and Thai communities of Cleveland. Further ambiguities with the term can include Chinese ethnoburbs which by definition are… Suburban ethnic clusters of residential areas and business districts in large metropolitan areas[7] where the intended purpose is to be… As isolated from the white population as Hispanics. [8] An article in The New York Times blurs the line further by categorizing very different Chinatowns such as Chinatown, Manhattan, which exists in an urban setting as “traditional”; Monterey Park’s Chinatown, which exists in a “suburban” setting (and labeled as such); and Austin, Texas’s Chinatown, which is in essence a “fabricated” Chinese-themed mall. This contrasts with narrower definitions, where the term only described Chinatown in a city setting. In some cities in Spain, the term barrio chino (‘Chinese quarter’) denotes an area, neighborhood or district where prostitution or other businesses related to the sex industry are concentrated; i. Some examples of this are the Chinatown of Salamanca and Barri Xinès, the Chinatown of Barcelona a part of El Raval, although in Barcelona there was a small Chinese community in the 1930s. See also: Chinese emigration. Trading centres populated predominantly by Chinese men and their native spouses have long existed throughout Southeast Asia. Emigration to other parts of the world from China accelerated in the 1860s with the signing of the Treaty of Peking (1860), which opened the border for free movement. Early emigrants came primarily from the coastal provinces of Guangdong (Canton, Kwangtung) and Fujian (Fukien, Hokkien) in southeastern China – where the people generally speak Toishanese, Cantonese, Hakka, Teochew (Chiuchow) and Hokkien. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, a significant amount of Chinese emigration to North America originated from four counties called Sze Yup, located west of the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong province, making Toishanese a dominant variety of the Chinese language spoken in Chinatowns in Canada and the United States. As conditions in China have improved in recent decades, many Chinatowns have lost their initial mission, which was to provide a transitional place into a new culture. As net migration has slowed into them, the smaller Chinatowns have slowly decayed, often to the point of becoming purely historical and no longer serving as ethnic enclaves. The Chinese New Year celebrated in Chinatown, Kolkata. Along the coastal area of Southeast Asia of the 16th century, quite many Chinese settlements existed in according to Zheng He’s and Tome Pires’ travel accounts. Melaka in Portuguese colonial period, for instance, had a large number of Chinese population in Campo China. They settled down at port towns under authority’s approval for trading. After the European colonial powers seized and ruled the port towns in the 16th century, Chinese supported European traders and colonists, and created autonomic settlements. Several Asian Chinatowns, although not yet called by that name, have a long history. Those in Nagasaki, Kobe and Yokohama, Japan, [11] Binondo in Manila, Hoi An and Bao Vinh in central Vietnam[12] all existed in 1600. Glodok, the Chinese quarter of Jakarta, Indonesia, dates to 1740. Chinese presence in India dates back to the 5th century AD, with the first recorded Chinese settler in Calcutta named Young Atchew around 1780. [14] Chinatowns first appeared in the Indian cities of Calcutta (now renamed Kolkata), Mumbai and Chennai. The Chinatown centered on Yaowarat Road in Bangkok, Thailand, was founded at the same time as the city itself, in 1782. Chinese seamen established one of the earliest Chinatowns around the docks in Liverpool in the mid-19th century. An early enclave of Chinese people emerged in the 1830s in Liverpool, England, when the first direct trading vessel from China arrived in Liverpool’s docks to trade in goods, including silk and cotton wool. [16] They settled near the docks, but the area was heavily bombed during World War II, with the Chinese community moving a few blocks to the current Liverpool Chinatown in Nelson Street. The Chinatown in San Francisco is one of the largest in North America and the oldest north of Mexico. It served as a port of entry for early Chinese immigrants from the 1850s to the 1900s. [17] The area was the one geographical region deeded by the city government and private property owners which allowed Chinese persons to inherit and inhabit dwellings within the city. Many Chinese found jobs working for large companies seeking a source of labor, most famously as part of the Central Pacific[18] on the Transcontinental Railroad. Since it started in Omaha, that city had a notable Chinatown for almost a century. [19] Other cities in North America where Chinatowns were founded in the mid-nineteenth century include almost every major settlement along the West Coast from San Diego to Victoria. Other early immigrants worked as mine workers or independent prospectors hoping to strike it rich during the 1849 Gold Rush. Economic opportunity drove the building of further Chinatowns in the United States. The initial Chinatowns were built in the Western United States in states such as California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. As the transcontinental railroad was built, more Chinatowns started to appear in railroad towns such as St. Louis, Chicago, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Butte Montana, and many east coast cities such as New York City, Boston, Philadelphia, Providence, and Baltimore. With the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, many southern states such as Arkansas, Louisiana, and Georgia began to hire Chinese for work in place of slave labor. The history of Chinatowns was not always peaceful, especially when labor disputes arose. Racial tensions flared when lower-paid Chinese workers replaced white miners in many mountain-area Chinatowns, such as in Wyoming with the Rock Springs Massacre. Many of these frontier Chinatowns became extinct as American racism surged and the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed. In Australia, the Victorian gold rush which began in 1851 attracted Chinese prospectors from the Guangdong area, and a community began to form in the eastern end of Little Bourke Street, Melbourne by the mid 1850s; the area is still the centre of the Melbourne chinatown, making it the oldest continuously occupied Chinatown in a western city (since the San Francisco one was destroyed and rebuilt). Gradually expanding, it reached a peak in the early 20th century, with Chinese business, mainly furniture workshops, occupying a block wide swath of the city, overlapping into the adjacent’Little Lon’ red light district. With restricted immigration it shrunk again, becoming a strip of Chinese restaurants by the late 1970s, when it was celebrated with decorative arches, and with recent huge influx of students from mainland China is now the centre of a much larger area of noodle shops, travel agents, restaurants, and groceries. The Australian gold rushes also saw the development of a Chinatown in Sydney, at first around the Rocks, near the docks, but it has moved twice, first in the 1890s to the east side of the Haymarket area, near the new markets, then in the 1920s concentrating on the west side, [21] and Chinatown, Sydney is now centred on Dixon Street. Other Chinatowns in European capitals, including Paris and London, were established at the turn of the 20th century. The first Chinatown in London was located in the Limehouse area of the East End of London[22] at the start of the 20th century. The Chinese population engaged in business which catered to the Chinese sailors who frequented the Docklands. The area acquired a bad reputation from exaggerated reports of opium dens and slum housing. France received a large settlement of Chinese immigrant laborers, mostly from the city of Wenzhou, in the Zhejiang province of China. Significant Chinatowns sprung up in Belleville and the 13th arrondissement of Paris. Manhattan’s Chinatown, the largest concentration of Chinese people in the Western Hemisphere[23]. Chinatown, San Francisco, the oldest Chinatown in North America. Liverpool’s Chinatown, the oldest Chinatown in Europe. Chinatown, Philadelphia, the recipient of significant Chinese immigration from both New York City[24] and China[25]. By the late 1970s, refugees and exiles from the Vietnam War played a significant part in the redevelopment of Chinatowns in developed Western countries. As a result, many existing Chinatowns have become pan-Asian business districts and residential neighborhoods. By contrast, most Chinatowns in the past had been largely inhabited by Chinese from southeastern China. In 2001, the events of September 11 have resulted in a mass migration of about 14,000 Chinese workers from Manhattan’s Chinatown to Montville, Connecticut, due to the fall of the garment industry and workers transitioning to casino jobs fueled by the development of the Mohegan Sun casino. In 2012, Tijuana’s Chinatown formed as a result of availability of direct flights to China. The La Mesa District of Tijuana was formerly a small enclave, but has tripled in size as a result of direct flights to Shanghai, with an ethnic Chinese population rise from 5,000 in 2009 to roughly 15,000 in 2012, overtaking Mexicali’s Chinatown as the largest Chinese enclave in Mexico. The busy intersection of Main Street, Kissena Boulevard, and 41st Avenue in the Flushing Chinatown , Queens, New York City. The segment of Main Street between Kissena Boulevard and Roosevelt Avenue, punctuated by the Long Island Rail Road trestle overpass, represents the cultural heart of Flushing Chinatown. Housing over 30,000 individuals born in China alone, the largest by this metric outside Asia, Flushing has become home to the largest and one of the fastest-growing Chinatowns in the world. The New York metropolitan area, consisting of New York City, Long Island, and nearby areas within the states of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania, is home to the largest Chinese American population of any metropolitan area within the United States and the largest Chinese population outside of China, enumerating an estimated 893,697 in 2017[27] and including at least 12 Chinatowns. Continuing significant immigration from Mainland China, both legal[28][29] and illegal[30] in origin, has spurred the ongoing rise of the Chinese American population in the New York metropolitan area; this immigration continues to be fueled by New York’s status as an alpha global city, its high population density, its extensive mass transit system, and the New York metropolitan area’s enormous economic marketplace. The Manhattan Chinatown contains the largest concentration of ethnic Chinese in the Western hemisphere;[31] while the Flushing Chinatown in Queens has become the world’s largest Chinatown, but conversely, has also emerged as the epicenter of organized prostitution in the United States. Today, Chinatown, Chicago is one of the few Chinatown neighborhoods in the United States that has shielded gentrification and has seen a continued growth of Chinese residents. People of Fujian province used to move over the South China Sea from the 14th century to look for more stable jobs, in most cases of trading and fishery, and settled down near the port/jetty under approval of the local authority such as Magong (Penghu), Lukang (Taiwan), Hoian (Vietnam), Songkla (Thailand), Malacca (Malaysia), Banten, Semarang, Tuban (Indonesia), Manila (the Philippines), etc. A large number of this kind of settlements was developed along the coastal areal of the South China Sea, and was called “Campon China” by Portuguese account[34] and “China Town” by English account. The settlement was developed along jetty and protected by Mazu temple, which was dedicated for a goddess for safe sailing. Market place was open in front of Mazu temple, and shophouses were built along the street leading from west side of the Mazu temple. At the end of the street, Tudigong (Land God) temple was placed. As the settlement prospered as commercial town, Kuan Ti temple would be added for commercial success, especially by people from Hong Kong and Guangdong province. This core pattern was maintained even the settlement got expanded as a city, and forms historical urban center of the Southeast Asia. Hoian Settlement Pattern, Vietnam, 1991. Pengchau Settlement Pattern, Hong Kong, 1991. Chinese Settlement in Georgetown, Malaysia, 1991. Chinese Settlement in Kuching, Malaysia, 1991. Tin Hua (Goddess of Mercy) Temple in Kucing, Malaysia, 1991. To Di Gong (Land God) Temple at Kucing, 1991. The features described below are characteristic of many modern Chinatowns. The early Chinatowns such as those in San Francisco and Los Angeles in the United States were naturally destinations for people of Chinese descent as migration were the result of opportunities such as the California Gold Rush and the Transcontinental Railroad drawing the population in, creating natural Chinese enclaves that were almost always 100% exclusively Han Chinese, which included both people born in China and in the enclave, in this case American-born Chinese. [37] In some free countries such as the United States and Canada, housing laws that prevent discrimination also allows neighborhoods that may have been characterized as “All Chinese” to also allow non-Chinese to reside in these communities. For example, the Chinatown in Philadelphia has a sizeable non-Chinese population residing within the community. [38] A recent study also suggests that the demographic change is also driven by gentrification of what were previously Chinatown neighborhoods. The influx of luxury housing is speeding up the gentrification of such neighborhoods. The trend for emergence of these types of natural enclaves is on the decline (with the exceptions being the continued growth and emergence of newer Chinatowns in Queens and Brooklyn in New York City), only to be replaced by newer “Disneyland-like” attractions, such as a new Chinatown that will be built in the Catskills region of New York. [39] This includes the endangerment of existing historical Chinatowns that will eventually stop serving the needs of Chinese immigrants. Newer developments like those in Norwich, Connecticut, and the San Gabriel Valley, which are not necessarily considered “Chinatowns” in the sense that they do not necessarily contain the Chinese architectures or Chinese language signs as signatures of an officially sanctioned area that was designated either in law or signage stating so, differentiate areas that are called “Chinatowns” versus locations that have “significant” populations of people of Chinese descent. For example, San Jose, California in the United States has 63,434 people 2010 U. Census of Chinese descent, and yet “does not have a Chinatown”. Some “official” Chinatowns have Chinese populations much lower than that. Main article: Chinese architecture. Many tourist-destination metropolitan Chinatowns can be distinguished by large red arch entrance structures known in Mandarin Chinese as Paifang (sometimes accompanied by imperial guardian lion statues on either side of the structure, to greet visitors). Other Chinese architectural styles such as the Chinese Garden of Friendship in Sydney Chinatown and the Chinese stone lions at the gate to the Victoria, British Columbia Chinatown are present in some Chinatowns. Mahale Chiniha, the Chinatown in Iran, contains many buildings that were constructed in the Chinese architectural style. Paifangs usually have special inscriptions in Chinese. Historically, these gateways were donated to a particular city as a gift from the Republic of China and People’s Republic of China, or local governments (such as Chinatown, San Francisco), and business organizations. The long-neglected Chinatown in Havana, Cuba, received materials for its paifang from the People’s Republic of China as part of the Chinatown’s gradual renaissance. Construction of these red arches is often financed by local financial contributions from the Chinatown community. Some of these structures span an entire intersection, and some are smaller in height and width. Some paifang can be made of wood, masonry, or steel and may incorporate an elaborate or simple design. Entrance to Chinatown, Sydney. Paifang in Buenos aires, Argentina. Chinatown, Boston looking towards the paifang. Gate of Chinatown, Portland, Oregon. Chinatown entry arch in Newcastle, England. Chinese Garden of Friendship, part of Sydney Chinatown. Chinese stone lions at the Chinatown gate in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. Harbin Gates in Chinatown of Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Millennium Gate on Pender Street in Chinatown of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Chinese Cultural Centre in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Chinese Temple “Toong On Church” in Kolkata, India. Chinese Temple in Yokohama Chinatown, Japan. Main article: Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association. Headquarters of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association in Chinatown, San Francisco. A major component of many Chinatowns is the family benevolent association, which provides some degree of aid to immigrants. These associations generally provide social support, religious services, death benefits (members’ names in Chinese are generally enshrined on tablets and posted on walls), meals, and recreational activities for ethnic Chinese, especially for older Chinese migrants. Membership in these associations can be based on members sharing a common Chinese surname or belonging to a common clan, spoken Chinese dialect, specific village, region or country of origin, and so on. Many have their own facilities. Some examples include San Francisco’s prominent Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (Zhonghuá Zong Huìguan), aka Chinese Six Companies, and Los Angeles’ Southern California Teochew Association. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association is among the largest umbrella groups of benevolent associations in the North America, which branches in several Chinatowns. Politically, the CCBA has traditionally been aligned with the Kuomintang and the Republic of China. The London Chinatown Chinese Association is active in Chinatown, London. Chinatown, Paris has an institution in the Association des Résidents en France d’origine indochinoise and it servicing overseas Chinese immigrants in Paris who were born in the former French Indochina. Traditionally, Chinatown-based associations have also been aligned with ethnic Chinese business interests, such as restaurant, grocery, and laundry (antiquated) associations in Chinatowns in North America. In Chicago’s Chinatown, the On Leong Merchants Association was active. Official signs in Boston pointing towards “Chinatown”. Although the term “Chinatown” was first used in Asia, it does not come from a Chinese language. Its earliest appearance seems to have been in connection with the Chinese quarter of Singapore, which by 1844 was already being called “China Town” or “Chinatown” by the British colonial government. [41][42] This may have been a word-for-word translation into English of the Malay name for that quarter, which in those days was probably “Kampong China” or possibly “Kota China” or “Kampong Tionghua/Chunghwa/Zhonghua”. The first appearance of a Chinatown outside Singapore may have been in 1852, in a book by the Rev. Hatfield, who applied the term to the Chinese part of the main settlement on the remote South Atlantic island of St. [43] The island was a regular way-station on the voyage to Europe and North America from Indian Ocean ports, including Singapore. Sign inside Jefferson Station in Philadelphia pointing to “Chinatown”. One of the earliest American usages dates to 1855, when San Francisco newspaper The Daily Alta California described a “pitched battle on the streets of [SF’s] Chinatown”. [44] Other Alta articles from the late 1850s make it clear that areas called “Chinatown” existed at that time in several other California cities, including Oroville and San Andres. [45][46] By 1869, Chinatown had acquired its full modern meaning all over the U. For instance, an Ohio newspaper wrote: From San Diego to Sitka… Every town and hamlet has its’Chinatown’. In British publications before the 1890s, “Chinatown” appeared mainly in connection with California. At first, Australian and New Zealand journalists also regarded Chinatowns as Californian phenomena. However, they began using the term to denote local Chinese communities as early as 1861 in Australia[48] and 1873 in New Zealand. [49] In most other countries, the custom of calling local Chinese communities “Chinatowns” is not older than the twentieth century. Several alternate English names for Chinatown include China Town (generally used in British and Australian English), The Chinese District, Chinese Quarter, and China Alley (an antiquated term used primarily in several rural towns in the western United States for a Chinese community; some of these are now historical sites). In the case of Lillooet, British Columbia, Canada, China Alley was a parallel commercial street adjacent to the town’s Main Street, enjoying a view over the river valley adjacent and also over the main residential part of Chinatown, which was largely of adobe construction. All traces of Chinatown and China Alley there have disappeared, despite a once large and prosperous community. Street sign in Chinatown, Newcastle, with below the street name. In Chinese, Chinatown is usually called , in Cantonese Tong jan gai, in Mandarin Tángrénjie, in Hakka Tong ngin gai, and in Toisan Hong ngin gai, literally meaning “Tang people’s street(s)”. The Tang Dynasty was a zenith of the Chinese civilization, after which some Chinese call themselves. Some Chinatowns are indeed just one single street, such as the relatively short Fisgard Street in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. A more modern Chinese name is (Cantonese: Waa Fau, Mandarin: Huábù) meaning “Chinese City”, used in the semi-official Chinese translations of some cities’ documents and signs. Bù, pronounced sometimes in Mandarin as fù, usually means seaport; but in this sense, it means city or town. Tong jan fau (“Tang people’s town”) is also used in Cantonese nowadays. The literal word-for-word translation of Chinatown-Zhongguó Chéng is also used, but more frequently by visiting Chinese nationals rather than immigrants of Chinese descent who live in various Chinatowns. Chinatowns in Southeast Asia have unique Chinese names used by the local Chinese, as there are large populations of people who are Overseas Chinese, living within the various major cities of Southeast Asia. As the population of Overseas Chinese, is widely dispersed in various enclaves, across each major Southeast Asian city, specific Chinese names are used instead. For example, in Singapore, where 2.8 million ethnic Chinese constitute a majority 74% of the resident population, [50] the Chinese name for Chinatown is Niúcheshui (, Hokkien POJ: Gû-chia-chúi), which literally means “ox-cart water” from the Malay’Kreta Ayer’ in reference to the water carts that used to ply the area. The Chinatown in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, (where 2 million ethnic Chinese comprise 30% of the population of Greater Kuala Lumpur [51]) while officially known as Petaling Street (Malay: Jalan Petaling), is referred to by Malaysian Chinese by its Cantonese name ci4 cong2 gaai1 (, pinyin: Cíchang Jie), literally “tapioca factory street”, after a tapioca starch factory that once stood in the area. In Manila, Philippines, the area is called Mínlúnluò Qu , literally meaning the “Mín and Luò Rivers confluence district” but is actually a transliteration of the local term Binondo and an allusion to its proximity to the Pasig River. In Francophone regions (such as France and Quebec), Chinatown is often referred to as le quartier chinois (the Chinese Quarter; plural: les quartiers chinois). The most prominent Francophone Chinatowns are located in Paris and Montreal. The Spanish-language term is usually barrio chino (Chinese neighborhood; plural: barrios chinos), used in Spain and Latin America. However, barrio chino or its Catalan cognate barri xinès do not always refer to a Chinese neighborhood: these are also common terms for a disreputable district with drugs and prostitution, and often no connection to the Chinese. The Vietnamese term for Chinatown is Khu ngu? I Hoa (Chinese district) or ph? Tàu (Chinese street). Vietnamese language is prevalent in Chinatowns of Paris, Los Angeles, Boston, Philadelphia, Toronto, and Montreal as ethnic Chinese from Vietnam have set up shop in them. In Japanese, the term “chukagai” (, literally “Chinese Street”) is the translation used for Yokohama and Nagasaki Chinatown. In Indonesia, chinatown is known as Pecinan, a shortened term of pe-cina-an, means everything related to the Chinese people. Most of these pecinans usually located in Java. Some languages have adopted the English-language term, such as Dutch and German. Street scene of the Chinatown in Cyrildene, Johannesburg. Main article: Chinatowns in Africa. There are three noteworthy Chinatowns in Africa located in the coastal African nations of Madagascar, Mauritius, and South Africa. South Africa has the largest Chinatown and the largest Chinese population of any African country and remains a popular destination for Chinese immigrants coming to Africa. Derrick Avenue in Cyrildene, Johannesburg, hosts South Africa’s largest Chinatown. Main article: Chinatowns in the Americas. In the Americas, which includes North America, Central America and South America, Chinatowns have been around since the 1800s. The most prominent ones exist in the United States and Canada in Toronto, New York City, San Francisco, and Vancouver. The New York City metropolitan area is home to the largest ethnic Chinese population outside of Asia, comprising an estimated 893,697 uniracial individuals as of 2017, [53] including at least 12 Chinatowns – six[54] (or nine, including the emerging Chinatowns in Corona and Whitestone, Queens, [55] and East Harlem, Manhattan) in New York City proper, and one each in Nassau County, Long Island; Edison, New Jersey;[55] and Parsippany-Troy Hills, New Jersey, not to mention fledgling ethnic Chinese enclaves emerging throughout the New York City metropolitan area. San Francisco, a Pacific port city, has the oldest and longest continuous running Chinatown in the Western Hemisphere. [56][57][58] In Canada, Vancouver’s Chinatown is the country’s largest. The oldest Chinatown in the Americas is in Mexico City and dates back to at least the early 17th century. [60] Since the 1970s, new arrivals have typically hailed from Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. Latin American Chinatowns may include the descendants of original migrants – often of mixed Chinese and Latin parentage – and more recent immigrants from East Asia. Most Asian Latin Americans are of Cantonese and Hakka origin. Estimates widely vary on the number of Chinese descendants in Latin America. Notable Chinatowns also exist in Lima, Peru. Chinatowns in the Americas. San Francisco’s Chinatown. Portland, Oregon’s Chinatown. Chinatown in Canada’s Capital, Ottawa. Arch honors Chinese-Mexican community of Mexico City, built in 2008, Articulo 123 Street. Main article: Chinatowns in Asia. Chinatowns in Asia are widespread with a large concentration of overseas Chinese in East Asia and Southeast Asia and ethnic Chinese whose ancestors came from southern China – particularly the provinces of Guangdong, Fujian, and Hainan – and settled in countries such as Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam centuries ago-starting as early as the Tang Dynasty, but mostly notably in the 17th through the 19th centuries (during the reign of the Qing Dynasty), and well into the 20th century. Today the Chinese diaspora in Asia is largely concentrated in Southeast Asia however the legacy of the once widespread overseas Chinese communities in Asia is evident in the many Chinatowns that are found across East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Yokohama Chinatown’s Goodwill Gate in Japan. Kan Yin Temple (Kwan Yin Si), a place of worship for Burmese Chinese in Bago, also serves as a Mandarin school. Chinatown gate in Mangga Dua, Jakarta, Indonesia. Kya-Kya or Kembang Jepun, Surabaya’s Chinatown, one of oldest Chinatown in Indonesia. Chinese New Year celebrated in Chinatown, Kolkata, India. Main articles: Chinatowns in Australia and Chinatowns in Oceania. The Chinatown of Melbourne lies within the Melbourne Central Business District and centers on the eastern end of Little Bourke Street. It extends between the corners of Swanston and Exhibition Streets. Melbourne’s Chinatown originated during the Victorian gold rush in 1851, and is notable as the oldest Chinatown in Australia. It has also been claimed to be the longest continuously running Chinese community outside of Asia, but only because the 1906 San Francisco earthquake all but destroyed the Chinatown in San Francisco in California. Sydney’s main Chinatown centers on Sussex Street in the Sydney downtown. It stretches from Central Station in the east to Darling Harbour in the west, and is Australia’s largest Chinatown. The Chinatown of Adelaide was originally built in the 1960s and was renovated in the 1980s. It is located near Adelaide Central Market and the Adelaide Bus Station. Chinatown Gold Coast is a precinct in the Central Business District of Southport, Queensland, that runs through Davenport Street and Young Street. The precinct extends between Nerang Street in the north and Garden Street/Scarborough Street east-west. Redevelopment of the precinct was established in 2013 and completed in 2015 in time for Chinese New Year celebrations. There are additional Chinatowns in Brisbane, Perth and Broome in Australia. Chinatowns in Australia and Oceania. Paifang at Sydney Chinatown. Paifang at Bendigo Chinese Precinct. Melbourne Chinatown entrance at Little Bourke Street. Main article: Chinatowns in Europe. Several urban Chinatowns exist in major European capital cities. There is Chinatown, London, England as well as major Chinatowns in Birmingham, Liverpool, Newcastle, and Manchester. Berlin, Germany has one established Chinatown in the area around Kantstrasse of Charlottenburg in the West. Antwerp, Belgium has also seen an upstart Chinese community, that has been recognized by the local authorities since 2011. [61] The city council of Cardiff has plans to recognize the Chinese Diaspora in the city. The Chinatown in Paris, located in the 13th arrondissement, is the largest in Europe, where many Vietnamese – specifically ethnic Chinese refugees from Vietnam – have settled and in Belleville in the northeast of Paris as well as in Lyon. In Italy, there is a Chinatown in Milan between Via Luigi Canonica and Via Paolo Sarpi and others in Rome and Prato. In the Netherlands, Chinatowns exist in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and the Hague. In the United Kingdom, several exist in Birmingham, Liverpool, London, Manchester and Newcastle Upon Tyne. The Chinatown in Liverpool is the oldest Chinese community in Europe. [63] The Chinatown in London was established in the Limehouse district in the late 19th century. The Chinatown in Manchester is located in central Manchester. Map of Chinatown Milan. Gate of Chinatown, Liverpool England, is the largest multiple-span arch outside of China, in the oldest Chinese community in Europe. Wardour Street, Chinatown, London. Chinese Quarter in Birmingham, England. Chinese new year celebration in Lyon, France. Chinatowns have been referenced in various films including The Joy Luck Club, Big Trouble in Little China, Year of the Dragon and Chinatown. Also, many films in which Jackie Chan appears reference locations in Chinatown, particularly the Rush Hour series with Chris Tucker. Chinatowns have also been mentioned in the song “Kung Fu Fighting” by Carl Douglas whose song lyrics says… There was funky China men from funky Chinatown… The martial arts actor Bruce Lee is well known as a person who was born in the Chinatown of San Francisco. [65] Other notable Chinese Americans such as politician Gary Locke and NBA player Jeremy Lin grew up in suburbs with lesser connections to traditional Chinatowns. Neighborhood activists and politicians have increased in prominence in some cities, and some are starting to attract support from non-Chinese voters. Wikimedia Commons has media related to. Africans in Guangzhou, the largest people of the African diaspora living in China. Europe Street, a street in China dedicated to European culture. Jack Manion San Francisco’s Chinatown squad. Cities with significant Chinese-American populations. List of named ethnic enclaves in North American cities. Chinatowns in the United States.