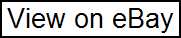

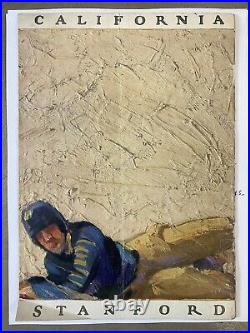

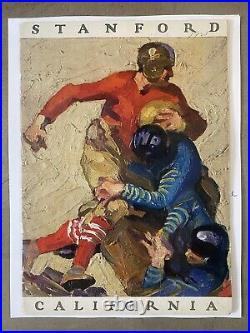

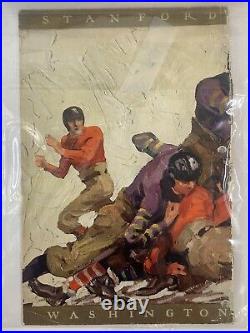

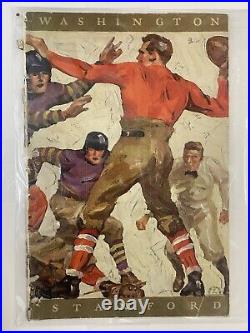

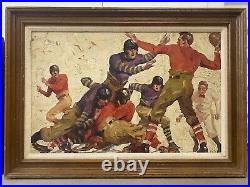

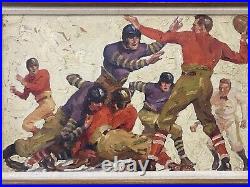

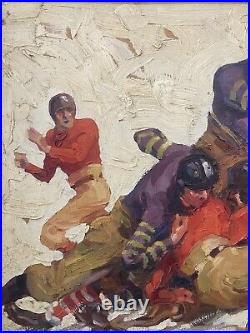

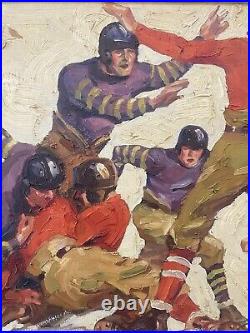

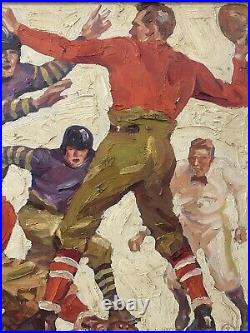

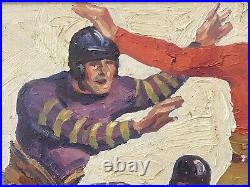

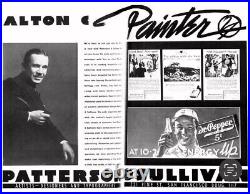

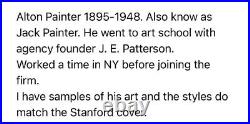

These are two original Historic Vintage Old 1920s Ivy League STANFORD College FOOTBALL Oil Paintings on Artist Board, that were famously published as the brochures for the football games between Stanford vs. Cal “Berkely” THE BIG GAME (1925) & Stanford vs. These paintings were produced by Patterson & Sullivan of San Francisco known as P&H Creative Group today. The painting on the left is signed “Painter” in the upper left corner, which relates to Alton “Jack” Painter (1895 – 1948), a California commercial artist, as the author behind these pieces. The artwork on the right displays the swan-in-circle signature painted in the lower right corner, which was and still is the logo for Patterson & Sullivan P&H Creative Group. Rare original vintage copies of the 1925 & 1926 Stanford football game brochures, which prominently feature these paintings on the front and back covers, will be included in this sale, as additional provenance and free bonus gifts. They are in fair condition for their age and use. The painting on the left Stanford vs. CAL, 1925 is approximately 12 x 18 3/4 inches including frame. Actual visible artwork is approximately 13 1/8 x 19 7/8 inches. The painting on the right (Stanford vs Washington, 1926) is approximately. 15 3/4 x 22 3/4 inches. Actual visible artwork is approximately 11 3/4 x 18 3/8 inches. These pieces are in very good condition for nearly a century of age and storage, with mild scuffing and edge wear to the frames, and moderate spots of paint loss to the white sky area of the painting on the right please see photos. The 1925 “Big Game” famously featured football legends Pop Warner, Ernie Nevers, Tut Imlay, Andy Smith & Ted Shipkey. These original paintings are the Holy Grail for an early Stanford or Ivy League Football collector. They are extraordinarily rare and belong in a museum. I will give special consideration to any offers from museum institutions. Acquired from an old private collection in Northern California. If you like what you see, I encourage you to make an Offer. Please check out my other listings for more wonderful and unique artworks! 1895 – Reno, Nevada. 1948 – Berkeley, California. Alton Painter (1895 – 1948) was active/lived in California, New York, Nevada. Alton Painter is known for Commercial Art; Painting. Born in Reno, NV on July 20, 1895. Painter moved to California with his family in 1908. Coming from NYC, he arrived in Oakland in 1934, and then joined a group of artists called The Thirteen Watercolorists (formed by Maurice Logan and Maynard Dixon). He was active in the San Francisco Bay area until his demise in Berkeley on Jan. Drawn to the Action. For decades, some of the West Coast’s top illustrators made it their business to combine pigskin and pigment. Christina Yoon (Stanford Magazine). For more than 30 years starting in 1925, Stanford football fans were treated to art while they sat in the stands. The covers of programs for football games against long-time rivals such as Cal and USC were illustrated with paintings by the artists at Patterson & Sullivan. The company, now called P&H Creative Group, was the largest illustrative service firm on the West Coast at the time. “Maybe someone had a Stanford connection, ” says Bruce Hettema, the company’s current owner. Or maybe the firm’s artists sought out a way to take a break from illustrating corporate brochures. Sadly, there wasn’t much value placed on them at the time, so lots of them were thrown away. Hettema says P&H’s current artists often find inspiration in these relics. We’ve been able to put flavors of the past in our current work. Stanford vs Cal: A Brief History of the Big Game. Chronicling the highs and lows of Stanford’s greatest rivalry. Welcome to a Brief History of Big Game. In honor of the 120. Playing of this great rivalry, I’ll be looking back at some of the highlights that dot its illustrious history. The rivalry between the Stanford Cardinal. And California Golden Bears. Is a special one. It is the oldest rivalry played on the West Coast, predating the Apple Cup and Civil War by a couple of years, and the USC-UCLA rivalry by decades. The Big Game has featured some of the greatest players and most memorable plays in the history of football. Both schools have been very competitive against one another, sometimes mirror opposites. Cal claims more national championships in football, but Stanford has more conference championships and Rose Bowl victories. Cal has more all-time wins, but Stanford has a higher winning percentage. Stanford has had more all-Americans and NFL draft picks, but Cal has had more first round draft picks. Stanford has had one Heisman Trophy winner. The Stanford-Cal rivalry extends across all sports, and both schools are in competition as two of the greatest universities in the world. Stanford University regularly places among the very best schools in world rankings, spoken in the same breath as Harvard, MIT, CalTech, and the Oxbridge Universities of Great Britain. The University of California, Berkeley routinely places at the very top of the list of public universities in the world, and frequently places in the global top five alongside Stanford and its private school peers. Stanford and Cal easily have more Nobel Laureates than any other pair of schools playing major conference football and the competition isn’t even close. With their status among the greatest universities in the world and the geographic proximity that the schools share, staring at each other from opposite sides of the San Francisco Bay, a natural rivalry developed between Stanford and UC Berkeley that goes back nearly to the founding of both institutions. The sporting rivalry is a natural extension of this academic competition. In every sponsored and club sport that Stanford and Cal play, they consider each other their traditional and greatest rival. Still, the Big Game stands out as first among equals in all of the various sporting events between these schools. It is the absolute, must win game every year. No Stanford football season is truly successful without beating Cal, and our archrivals share the exact same feelings. The University of California began playing football all the way back in 1886, just 18 years after the founding of the school. Stanford University’s first team took the field in early 1892, just months after opening its doors. On March 19, 1892, Stanford and California would play their first ever game on a football field. Played at San Francisco’s Haight Street Grounds, Stanford beat California 14-10. Stanford undergrad Herbert Hoover helped to organize the event alongside Cal manager Herbert Lang. Later in the year, Stanford and California would play to a 10-10 tie in the second meeting between the two teams. Stanford won four of the first seven games, the rest were ties. California finally won their first contest in 1898. The Haight Street Grounds hosted the first thirteen meetings between the schools. The traditions were already developing, as the game was being played around Thanksgiving. It was the top sporting event in the city of San Francisco at the time and by 1900 it was already being referred to as the Big Game. The 1900 game was also the site of the deadliest spectator disaster at a sporting event in United States history, when dozens of men and boys fell through the roof of the San Francisco and Pacific Glass Works while they were watching the game. In all, 22 eventually died of their injuries and 78 were injured. The Big Game moved from the Haight Street Grounds to the home stadiums of each teams in 1904. Stanford led the series at the Grounds 5-4-4. The home and home pattern was set that year. Besides two games in the early 1920’s, the Big Game has been held in Berkeley on even years and at Stanford on odd years ever since. In 1906, Stanford and Cal, alongside many other universities, chose to drop sponsorship of football due to health concerns. Back then, unprotected players hurling themselves at each other resulted in a handful of deaths each year. To take the place of the Big Game, both schools adopted rugby in football’s stead. Both count the rugby meetings as official Big Games, but most football information sites don’t list them because, of course, they weren’t playing football. Stanford won five rugby games to Cal’s three with one tie. Cal began to sponsor football again in 1915 and helped to found the Pacific Coast Conference. Their Big Game from 1915 to 1917 was the game with Washington, while Stanford played Santa Clara in rugby. In 1918, Stanford finally restarted their football program and joined the PCC in 1919. With football back on, the Big Game would become the premier rivalry of the young conference. The 1918 Big Game is the only contest that hasn’t been recognized by either school, as Stanford was using volunteers who weren’t all students. Stanford lost that game 67-0. The period from the 1920’s to the 1940’s could be called the golden age of the Big Game. Very frequently, Stanford and Cal would be playing for conference and national championships, and their rivalry often played a huge part in the PCC’s Rose Bowl selection. Both schools were (mostly) led by a series of capable and successful coaches who brought out some of the best football the rivalry has seen. The 1920’s would be a high water mark for the Big Game, as both teams broke out into national prominence. Cal struck first, hiring Andy Smith in 1916. Smith took a couple of years to get things going at Berkeley, but when he did the Golden Bears became the first nationally prominent team to hail from the West Coast. Smith’s “Wonder Teams” went undefeated for five consecutive seasons from 1920 to 1924. The university claims the four seasons from 1920 to 1923 as a national championship campaigns. Needless to say, the Bears also dominated the Big Game. They shut out Stanford in three of those four championship years, with the fourth contest being a 42-7 drubbing of Stanford in the first ever game at the brand new Stanford Stadium in 1921. Cal’s 38-0 win in 1920 remains their largest margin of victory in the Big Game. In response to Cal’s dominance, Stanford hired Pop Warner in 1924. The architect of Pittsburgh’s national championship run in the 1910’s, Warner immediately produced results on The Farm. In his first season, an undefeated Stanford tied undefeated Cal 20-20 at Berkeley, and since Cal had already tied Washington earlier in the year, Stanford was able to win the PCC, though they lost to Note Dame 27-10 in the Rose Bowl. As a fun piece of trivia: Harold Lloyd’s classic silent film, The Freshman, was filmed on the field at halftime. Would be the last game Andy Smith coached. The legendary Bears head man died of pneumonia after the season at the age of 42. In 1926, Stanford beat Cal 41-6 to cap an undefeated season, they then tied Alabama in the Rose Bowl. Stanford and Alabama both claim 1926 as a national championship year. Warner reversed the trend that Smith had started at Cal. Whereas the Bears won five in a row over Stanford from 1919 to 1923, Stanford claimed five victories in six seasons (with one tie) from 1925 to 1930. The Big Game remained a fixture of PCC football in the 1930’s, and Stanford and Cal once again traded stretches of dominance. Pop Warner’s replacement, Tiny Thornhill, won the PCC in each of his first three seasons from 1933 to 1935 with his Vow Boys. The 1935 Big Game saw one loss Stanford shut out unbeaten Cal 13-0, stealing the Rose Bowl away from the Golden Bears. That 1935 Cal team was coached by Stub Allison, who would turn the tables on Stanford. Cal would win the PCC in three of the next four seasons, beating Stanford every time. Allison’s “Thunder Team” of 1937 went undefeated, winning the Big Game 13-0 in a game to decide the conference, and finished second in the second ever AP Poll. The Bears claim this unbeaten year as a national championship. It was the last time they won the Rose Bowl, a 13-0 victory over Alabama. The Big Game also saw a new tradition in the 1930’s, the reintroduction of the Stanford Axe. The Axe had been used by Stanford fans in 1899 at a rally to chop up a straw man wearing Cal colors and then at a baseball game against Berkeley held in San Francisco. After the game, the Axe was stolen by Cal fans and brought across the Bay on a ferry. It was held in a vault for 31 years and only taken out for Big Game and baseball rallies. In 1930, 21 Stanford fans plotted an elaborate scheme to regain the Axe that involved blinding flash bulbs, smoke bombs, Stanford fans dressed as Cal students, and three getaway cars. The successfully recaptured Axe was locked in a bank vault in Palo Alto while the universities negotiated on what to do with it, deciding to use the Axe as a travelling trophy for the winner of each Big Game starting in 1933. Nevertheless, the Axe has been stolen numerous times since, most recently in 1973. Thornhill was fired after the 1939 season in which the Indians went 1-7-1, and Allison’s contract wasn’t renewed after 1944’s 3-6-1 campaign. Thornhill’s replacement, Clark Shaughnessy, was a pioneer of the T formation that put Stanford right back on top. In 1940, Stanford’s “Wow Boys” went a clean 10-0, defeating Nebraska in the Rose Bowl 21-13 to cap their most recent unbeaten season. A few selectors believe that Stanford should claim the season as a national championship year, but the university so far has not. Shaughnessy left after the following season, seeing that Stanford would shut the program down due to the Second World War. Cal, who did not shut down their football program during the War, eventually settled on Pappy Waldorf as head coach in 1947. Waldorf would lead the Bears through their last truly great run. Called “Pappy’s Boys, ” the Bears won 33 consecutive regular season games from 1947 to 1950. The only thing keeping them from a national championship in the’48,’49, or’50 seasons was that they lost the Rose Bowl every year. In 1951, Stanford hired Chuck Taylor as head coach, and tasked him with stemming the losses to Berkeley that were again piling up. A member of Shaughnessey’s Wow Boys, Taylor saw immediate results. In the 1951 season, Stanford went undefeated into the Big Game, but lost to Cal 20-7 at home, ruining their perfect season. The Indians still made the Rose Bowl, as the Bears had already lost two conference games, but then lost to Illinois 40-7. Waldorf and Taylor remained on at their respective schools for the rest of the decade, but they were unable to sustain their early successes, the same problem had plagued Smith, Warner, Thornhill, and Allison. However, this time it would be a bit more permanent. The post-War boom helped to grow the State of California, but nowhere more than in Los Angeles. This demographic ballooning of Southern California had a drastic effect in football, as USC (who already was no stranger to success) and UCLA became the two most successful programs on the West Coast for the rest of the century. Stanford wouldn’t make the Rose Bowl for another 19 years. Pete Elliot’s 1958 Bears managed to make the Rose Bowl with a 7-3 record, but they were swept aside by Iowa. It is still Cal’s most recent appearance in the Grandaddy of Them All. The Big Game continued to be a hugely important affair despite the relative drop in stature of its two participants. With the conference championship usually already decided, the Stanford Axe became the real end of season prize for both teams, and sometimes the only thing worth playing for. If the 1920’s to the 1940’s was the golden age of the Big Game, then the 60’s through the 80’s was the silver age, where the bitter rivalry saw some of its most legendary exploits. The Big Game was as unpredictable as it was contentious, with the underdog seeming to upset the favored team just as often as not. Stanford and Cal both bottomed out in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s. It took the Indians nearly a decade to rebuild their program, and the Golden Bears took an even longer time to recover. With all of the social unrest at the Berkeley campus, the Cal football program took a back seat to student demonstrations, though they had a couple of good seasons. John Ralston finally got Stanford back to winning PAC-8 titles, but their first conference championship season under Ralston in 1970 was marred by a 22-14 loss at Memorial Stadium. The Indians shut out Cal 14-0 when they won the league in 1971. Ralston then left, and Stanford fell back to being another mediocre program. The early 1970’s marked a particularly exciting and competitive streak in the Big Game. In 1972, 2-8 Cal upset 6-4 Stanford on a last second touchdown pass to win 24-21. The next year, Stanford scored 13 points in the fourth quarter to beat Cal 26-17 in a back and forth scrum. The 1974 game is famous for Cardinals kicker Mike Langford’s 50 yard field goal, to seal a 22-20 upset of the #19 Bears at Memorial Stadium. The next year, Cal phenom quarterback Joe Roth squashed Stanford 48-15 at Stanford Stadium. In 1976, the Cardinals defeated Cal 27-24 on a last minute rally, and the players carried head coach Jack Christiansen off the field even though the university had fired him before the game. The Big Game continued like this for the next decade. With both teams rather irrelevant with USC, UCLA, and Washington battling for the PAC-10 title, the Big Game was the only thing that mattered. It was in this environment that one of the most famous and controversial events in college football’s long history occurred. 5-5 Stanford traveled to Berkeley to face 6-4 Cal. John Elway, the Cardinal’s senior quarterback, was playing for his first bowl game. Having kicked a field goal to take a 20-19 lead, Stanford left four seconds on the clock but drew an unsportsmanlike conduct penalty for excessive celebration. The Cardinal kicked from their own 25 yard line, and then all hell broke loose. In a series of five (disputed) laterals, the Bears moved the ball 55 yards into the endzone as time expired, past Stanford’s original 11 special teams players, other Stanford players that had ran onto the field, and members of the Leland Stanford Junior University Marching Band, who had stormed into the endzone anticipating victory. The play culminated in Cal’s Kevin Moen, recipient of the original kickoff and the fifth lateral, barreling over trombonist Gary Tyrell in the endzone. Now known simply as The Play, the ending of the 1982 Big Game is considered to be one of the most legendary events in football history. Stanford continues to dispute the ruling, arguing that the third lateral was illegal because the player was down before the ball left his hand, and that the fifth lateral was a forward pass. When Stanford has the Axe, the score is changed on the plaque to read a 20-19 Cardinal victory. Salving the embarrassment somewhat, Stanford got the better of Cal for most of the rest of the decade. 1988 was the last tie ever in the Big Game, as Bears kicker Robbie Keen’s last second field goal was blocked, leaving the Axe in the Cardinal’s possession. The 1990 Big Game is remembered for its wild finish, similar to that of The Play, the game is remembered by Stanford fans as “The Revenge of the Play” and The Payback. It was a see-saw affair. Cal led 25-18 with just seconds left when Stanford scored a touchdown. The Cardinal held the Axe, and would have kept it with a tie, but instead of kicking a field goal, head coach Denny Green went for a two-point conversion instead of the field goal. The attempt failed, and Stanford trailed 25-24 with 12 seconds left. Cal fans and players rushed the field in response and after the field was finally cleared the Cardinal, kicking off from midfield, were able to recover their onside kick on the Bears’ 37 yard line. Stanford QB Jason Palumbis was roughed up on his incomplete pass attempt, moving the ball to the 22 yard line. The Cardinal’s John Hopkins then kicked the game winning field goal as time expired. Stanford players and fans then stormed the field at Memorial Stadium. The 1990 Big Game was part of a larger trend in the series, in which long streaks began to take over from the back and forth craziness of the 70’s and 80’s. Including the tie in 1988, Stanford held the Axe for six years from 1987 to 1992. After many mediocre seasons in the 1980’s, Cal finally broke through and beat Bill Walsh’s Cardinal twice in a row in 1993 and 1994, the’93 win being a huge 46-17 debacle at Stanford Stadium. The streaks continued to calcify. Tyrone Willingham won seven straight games against Cal from 1995 to 2001. It was the longest unbroken winning streak in the history of the Big Game. Stanford had good teams and bad teams during Willingham’s tenure, but they always beat the Golden Bears. Willingham left in 2002, the same year Jeff Tedford came to Berkeley and completely reversed the trend. Cal won five in a row from 2002 to 2006 and seven of eight from’02 to’09. The Bears weren’t just lucky in those years, they were good. Cal achieved heights neither team had seen since the 1950’s, winning ten games twice in 2004 and 2006. They just couldn’t win the PAC-10 and make the Rose Bowl. Cal’s rise coincided with Stanford’s worst stretch of football since the 1960’s, but things would change once more. Jim Harbaugh came to The Farm in 2007, where he immediately endeared himself by upsetting USC and Cal. Just as Harbaugh began to build up the Cardinal, the Bears were starting to wane under Jeff Tedford. By 2009, Stanford was the team that was being upset. Cal’s 34-28 victory was the Cardinal’s only loss at Stanford Stadium that year. However, by 2010, the new dynamic had been set. Jim Harbaugh had transformed Stanford into a true powerhouse, and the Golden Bears were approaching the basement of the PAC-10. The Cardinal have beaten their archrivals in seven straight years and most of the time the margin has been comfortable. Since taking over for Harbaugh in 2011, David Shaw hasn’t yet lost to Cal. Stanford’s 63-13 win in 2013 was the largest margin of victory in the history of the Big Game. I have to admit, it seems as though this current streak has somewhat lessened the excitement for Big Game in recent years. Stanford fans now take beating our most hated rival as a given, and have been more preoccupied with defeating USC, Oregon, or Washington recently. Of course, this is all Cal’s fault for being so bad for so long. Once they get good, whenever that may be, I expect the Big Game to once again be the foremost thought on every Stanford fan’s mind. If and when that happens, let’s beat them anyway. The Cardinal’s recent success in the 1990’s and 2010’s has helped them earn winning records at both The Farm (30-21-1) and at Berkeley (28-20-6). Stanford leads the all-time series 63-45-11, you can read it right there on The Axe.