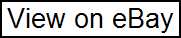

This vintage original photo captures the excitement and spirit of California University Football in 1930. Measuring 8 x 10 inches, this photograph features Lee Eisan in action. The image is a true representation of the era and will make a great addition to any collection. The photograph is a must-have for fans of universities and football. The original and licensed reprint ensures that you are getting a genuine piece of history. Add this collectible to your collection today! Lee was born in 1905 in San Francisco, CA; he was one of five children born to George M. The Eisans became one of the early pioneer families to settle in and around St. Helena in the Napa Valley. Lee became a star quarterback for the University of California Golden Bears and frequently appeared in the sports pages in California newspapers and sometimes in other states. He was described as a small man but’160 lb of speed and power. He was thought to be one of the smartest quarterbacks in college football during his career. His nickname was’Slippery Eel. Sun Herald (Biloxi, MS), 29 Oct 1929, p. Lee was the losing quarterback in the 1929 Rose Bowl game when the Golden Bears played Georgia Tech. That game is famous for perhaps the worst blunder in the history of college football. Roy’Wrong Way’ Riegels was the centre on the Golden Bears team and he ran 69 yards in the wrong direction, causing Georgia Tech to score and the Golden Bears to lose the game (8-7). Our Lee had a chance to score a touchdown in the third quarter… But he fell and failed to make the catch. The Tribune, 26 Sep 1929, p. Lee Eisan is in the lower right corner. At least he got to meet the president. His team played their semi-final game against the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia (which they won). Before the game, the team was invited to the White House to meet president Herbert Hoover. After he graduated from college, Lee became the head coach at various colleges in California. Lee was one of the referees for the 1942 Rose Bowl, played in Durham, North Carolina during World War II. The Duke Blue Devils played the Oregon State Beavers (Oregon won). The game was supposed to be played in Pasadena, CA but was moved to Durham because of fears the Japanese would bomb the west coast. Lee was given the honour of being the referee to do the game’s opening coin toss. Normally, it was done with a silver dollar, but Lee couldn’t find one so he borrowed a 50-cent piece from one of the Oregon players. After coaching college football for 40 years, Lee retired in 1971, but it only lasted one year. In 1972, at age 66, Lee became the Director of the San Francisco Olympic Club. The news story noted that he was only 10 lb over his playing weight of 165 lb. And he was’an impressive looking physical specimen. San Francisco Examiner, 9 Mar 1972, Page 52. Their engagement and marriage were widely reported in newspaper society columns. Edith seems to have been quite accomplished – newspapers often carried small articles about her theatrics and musical performances. They raised five children – Barbara, Michael, Leland, Daniel, and Winifred – in the San Francisco area. Oakland Tribune, 31 Jul 1930, p. Lee died in 1979 at age 75; he was survived by his wife, three sons, two daughters, two brothers (Alan, Leslie), one sister (Eleanor), and two grandchildren. Who is the only person who ever coached teams to both the Rose Bowl and the Final Four? The University of California’s Clarence “Nibs” Price. Nibs Price took over as Cal’s football head coach in 1926, after the death of Andy Smith. In his five years as head coach, he had three tremendous seasons and took the Bears to the 1929 Rose Bowl — where they were involved in possibly the most famous (or infamous) play in football history. And at the same time Price was coaching the football team, he was also the basketball head coach, ultimately winning more games than any coach in California basketball history, and earning a trip to the Final Four in 1946. Photobucket Clarence “Nibs” Price. “Nibs” Price was born in San Diego in 1890. In 1910 he was admitted to the University of California in Berkeley where, despite his short stature and slight build, he earned a varsity letter in rugby as well as baseball. He would have liked to have played football as well, but this was the era when American football had been replaced by rugby at Cal. Price was discharged from the service in Seattle in December 1918. On his way home to San Diego, he stopped off for a visit in Berkeley, where he met the new California head coach, Andy Smith. Smith was looking for an experienced football coach to take over the Bears’ freshman team. There was not a lot of talent to choose from, because most high schools and colleges had given up American football in the early 1900s, as a result of the extreme violence, injuries, and deaths resulting from the sport. But San Diego High School was one of the few schools which had never stopped playing the game. Smith thought Price would be good for Cal, both as an experienced football coach and as someone who might be able to convince the talented players at San Diego High School and other football schools to come to Cal. Price jumped at the chance to return to Berkeley, and was hired as an assistant coach on the spot. He would remain a Cal coach for the next 35 years. Hiring Nibs Price was one of the smartest decisions Andy Smith ever made, because Price turned out to be a great recruiter. Price convinced several of the best players he had coached at San Diego High School to come to Cal, among them Stan Barnes and Harold “Brick” Mueller, two of the greatest ever to play at Cal — or anywhere else. Price was also on good terms with players from other southern California high schools, against whom he had competed. He was able to use those personal ties to recruit Archie Nisbet, Don Nichols, Bill Bell and others to play for him on the Bears’ 1919 freshman team. The following year, it was these Nibs Price recruits who became the heart of California’s Wonder Teams. The Wonder Team set college football ablaze in 1920, with a perfect 9-0-0 record, including a dominating 28-0 win over Ohio State in the Rose Bowl. The team was undefeated again in 1921, and then again in 1922, establishing California as one of the great football powers in the nation. So great was the Wonder Team’s success, that Cal built a spectacular new stadium to hold the enormous crowds clamoring for tickets. Even after the first group of Wonder Team players graduated, the Bears continued to have great success under Andy Smith and his staff, completing two more undefeated seasons in 1923 and 1924. But things dropped off in 1925, with a decline in talent. The Bears went 6-3, suffering their first losses in six years. Still, Cal fans had unwavering faith that Andy Smith would return the Bears to glory within a year or two. But it was not to be. While on a visit to Philadelphia, Smith contracted pneumonia and died suddenly in January 1926. Andy Smith had stated several times that he thought Nibs Price was his natural successor as Cal’s head coach, and Price was duly elevated to that position in March 1926. Following the incomparable Andy Smith, especially in light of his sudden and shocking death, was an almost impossible task. To make things even more difficult for Price, he had also been named as Cal’s head basketball coach the previous year, and would now be responsible for coaching both teams. The 1926 season was not a promising start for Price’s Bears. The team had lost all of its best players to graduation, and it would probably have been a “re-building” year even if Andy Smith were still the head coach. Added to that, Smith’s death had cast a pall over the team, the fans, and the season. The Bears’ record was 3-6 — Cal’s first losing season in American football since 1897! The Bears did have a losing season in 1906, during the period when rugby had replaced football. And the season ended with a dismal 41-6 loss to undefeated Stanford. But despite the team’s problems in 1926, Nibs Price had the full support of his team and of Cal fans, who recognized what a difficult task he had had. In fact, Cal set an all-time attendance record that year, with 417,000 fans showing up at Memorial Stadium to watch the Bears. The fans’ confidence in Price was rewarded. The 1927 team, made up of now-experienced upperclassmen and a group of excellent sophomores newly elevated from the freshman team, made a much stronger showing. The season started with a 14-6 win over Santa Clara sparked by the surprising passing of unknown sophomore Benny Lom. The next week the Bears handed Nevada a resounding 54-0 defeat. Lom’s passing was the key again to Cal’s upset of St. Mary’s, and a 16-0 defeat of Oregon. The Bears were 5-0 going into the game against heavily favored USC in Los Angeles. The Trojans pulled out a 13-0 win, but the press called it one of the hardest-fought contests in memory. The Bears also lost to Stanford, but the 13-6 score was at least nowhere near as embarrassing as the prior year’s rout. Cal finished the season with a rare inter-sectional game against Pennsylvania, which was also highly favored. Price called plays which were very wide-open by the standards of the day, including a 40-yard pass from Benny Lom to Jim Dougery, resulting in a touchdown. Late in the game, Price called for a real razzle-dazzle play, with Paul Clymer throwing a pass to Paul Perrin, who then lateraled to Lee Eisen, who ran 42 yards for another touchdown. The stunning 27-13 Cal victory ended a successful 7-3 season that showed the Bears were back. 1928 would prove to be one of the most memorable seasons in Cal football history. Although the offense was a bit suspect, Nibs Price had a defense that was almost impenetrable. The Bears began the season with wins against Santa Clara, St. Mary’s, and Washington State, before facing a big test in the high-scoring USC team. A capacity crowd of more than 81,000 in Berkeley saw the Bears and the Trojans battle to a 0-0 tie. The star of the game was once again Benny Lom — but this time because of his outstanding punting! It was the first time USC had been shut out under head coach Howard Jones, and the Bears were pleased with their effort. The 1928 Bears were 6-1-1 going into the Big Game against another very high-scoring team. Once again the Cal defense came up strong, the big play being an interception and 75-yard run-back by Steve Bancroft for a Cal touchdown. The Bears were leading 13-7 late in the game, when disaster struck. With seconds left in the game, Stanford had the ball on Cal’s 24. Stanford quarterback Bill Simkin threw a bad pass, which Cal’s Irv Phillips could easily have intercepted. But Phillips thought it was fourth down, and just batted the ball down. On the next play, Stanford scored a touchdown to make the score 13-13. But the snap for the extra point was slow, giving Cal’s Frank Fitz time to smash through the Indians’ line and block the kick. The game ended in a tie. While this was certainly not as satisfying as a win, it was enough to send the 6-1-2 Bears to the Rose Bowl on New Year’s Day. The 1929 Rose Bowl between California and Georgia Tech turned out to be one of the most talked-about football games of all time. Once again, Cal’s defense was outstanding. And statistically, the Bears were ahead in every category, leading George Tech in: first downs 11-5; rushing yards 204-166; and passing yards 67-23. The only place Georgia Tech prevailed was the final score: 8-7. It was in this game, of course, that Cal’s Roy Riegels picked up a Georgia Tech fumble and started running toward the end zone. But Riegels had become confused and turned around, and he began running toward the wrong end zone. Teammate Benny Lom chased Riegels down the field, shouting at him to turn around, but he could not be heard over the roar of the crowd. Lom finally caught Riegels and tackled him on the Bears’ one-yard line. Although California had the ball first-and-ten on their own one-yard-line, the stunned Nibs Price ordered a punt on the next play. Calling a punt on first down was a fairly extraordinary thing to do, and Price’s call has remained highly controversial ever since. He was concerned that the Bears had been so demoralized by the Riegels play, that they might easily give up a safety on the one-yard line. And the Cal defense was so outstanding that he was confident they would not give up a score if they could just get a little room from a punt. But Price’s decision to punt only piled disaster onto disaster. The punt was blocked and rolled out of the end zone for a Georgia Tech safety — the very thing Price had been trying to avoid. And it was that safety that would turn out to be the margin of victory for Georgia Tech. Roy Riegels was in a state of shock. Price did not want to remove him from the game (he would not be allowed to come back in until after the half under the rules of the day), because he believed it would be a terrible blow to team morale. But he could not determine whether Riegels was injured or merely stunned by what had happened. So he took Riegels out and the young man sat on the bench trying to hold back tears as his teammates attempted to comfort him. Roy Riegels Wrong Way Run: a series of photos showing Riegels picking up the fumble, turning around, running toward the wrong end zone, and being chased down and tackled on the one-yard line by Benny Lom. And here is the film of the infamous run. Roy Riegels wrong way run in the Rose Bowl (via jjtiller). At halftime, Coach Price had to decide what to do with the devastated Riegels in the second half, as the young man sat sobbing in the corner of the locker room. Shortly before half-time ended, Price announced, Men, the same team that played in the first half will start the second. As the players started to run back onto the field, Riegels remained sitting where he was. When Price again told him he was going to start the second half, Riegels said, Coach, I can’t do it to save my life. I’ve ruined you, I’ve ruined the University of California, I’ve ruined myself. I couldn’t face that crowd in the stadium to save my life. ” Price put his hand on Riegels’ shoulder and said, “Roy, get up and go on back; the game is only half over. And Riegels went out and played what may have been the best half of football of his career. Unfortunately, Cal was not able to pull out the win, and Riegels become known forever as Wrong Way Riegels. However, Price’s vote of confidence in Riegels would pay off the following year, when he was elected captain by his teammates, and was named a first team All-American. And for the rest of his life, Roy Riegels made a point of sending letters to high school and college athletes who had made blunders which cost their teams a game, offering comfort, and letting them know that making such a mistake was not the end of the world. Cal Center Roy Riegels. Despite the great disappointment of the Rose Bowl loss on January 1, the 1929 football season would be Nibs Price’s best. The highlight of the year was once again the USC game. That game once again showed off Price’s willingness to take risks, when he called a fake punt from Cal’s own 15 yard line. Punter Benny Lom pulled the ball down and cut around the Trojan defender, who was blocked by Rusty Gill. Lom then dodged right between two more USC defenders, and ran 85 yards for the touchdown. A couple of series later, Roy Riegels blocked a Trojan punt through the end zone for a Cal safety. The final score was California 15, USC 7. Once again, the victory was won despite mediocre offense (USC out-gained the Bears 252 to 192, and the Bears punted 13 times), and because of outstanding defense and Price’s gamble on special teams. Cal’s Rusty Gill throws the block that will spring ball carrier Benny Lom for a 85-yard touchdown on a fake punt in the 1929 Cal-USC game. Although Cal ended the 1929 season with a 7-1-1 record, it was not entirely satisfying, because the one loss once again came against Stanford. A victory, or even a tie, in the Big Game would have sent the Bears back to the Rose Bowl. But as it was, California, Stanford, and USC ended the season tied for the conference championship. But virtually all of their great players graduated at the end of the 1929 season, including Benny Lom and first team All Americans Roy Riegels and Bert Schwarz. Even worse, 1930 began with a very bad omen when Stanford students disguised as reporters stole the Axe and spirited it away to Palo Alto. The 1930 Golden Bears started the season a mediocre 3-3. And then the axe fell. USC decided to take revenge for their loss the previous year, and utterly demolished the Bears, 74-0, running up 734 yards of total offense. 81 years later, this game still remains the worst loss in California history. An unfavorable editorial in The Daily Californian stirred up a media frenzy about the students trying to have Nibs Price fired. In fact, most students and fans still supported the coach, who had just completed three successful seasons. It was even reported in the papers that a prominent supporter of Coach Price had said, Let’s face it, fellows. We were beaten 74-0 by the best professional football team in the country. The president of USC expressed outrage, and threatened to break off all relations with the University of California, until Cal’s president, Robert Gordon Sproul, intervened to smooth things over. But the debacle against USC had definitely had consequences for the Bears. The next week, only 3,000 fans showed up at Memorial Stadium to watch Cal defeat a weak Nevada team 8-0. And the seemingly dispirited Bears were then crushed 41-0 by Stanford — a score which remains Cal’s worst Big Game defeat. The Bears’ record on the season was only 4-5, but Nibs Price resigned as head coach two days after the Big Game. Nibs Price’s career record as Cal’s head coach was 27-17-3. Three of his five seasons were highly successful, and he took the Bears to the 1929 Rose Bowl. His less-than-stellar rookie year can be attributed to the shock of Andy Smith’s death, and the graduation of many of the Bears’ best players. The loss of key players was also a big factor in the unsuccessful 1930 season, although the blow-outs by USC and Stanford were embarrassing. Yet there is no reason to think that Price could not have turned the team around if he had remained as head coach. He had a good group of new recruits coming in for 1931 and, in fact, the 1931 team would go 8-2, including a 6-0 victory over Stanford. It was entirely Price’s decision to resign as head coach. But he was by no means done at his beloved alma mater. Price actually remained on the football staff as an assistant under the new head coach, Bill Ingram, and under Ingram’s successors, including Stub Allison and Pappy Waldorf, coaching defensive backs and punters. Under Waldorf, he became the Bears’ head scout. Price’s football knowledge and recruiting abilities remained an important part of the Cal program for another 24 years. As a result, Nibs Price coached for seven of California’s eight Rose Bowl teams: in 1921 and 1922 as an assistant to Andy Smith, in 1929 as Cal’s head coach, in 1938 as an assistant to Stub Allison, and in 1949, 1950, and 1951 as an assistant to Pappy Waldorf. Nibs Price, who began his Cal football coaching career as an assistant on Andy Smith’s staff, ended it as an assistant to Pappy Waldorf. Pictured here is Waldorf’s first coaching staff. Back row: Eggs Manske, Nibs Price, Hal Grant, Wes Fry. Front row: Zeb Chaney, Pappy Waldorf, Bob Tessier. Price also remained on as Cal’s basketball head coach. He served in that position for an astonishing 30 seasons, from 1924 to 1954, when he was finally succeeded by Pete Newell. Price’s career record in basketball was 449-294, and his 449 career wins remains the Cal record. His 1946 team had a 30-6 record, and became the first Cal team to make it to the NCAA Final Four. Basketball head coach Nibs Price gives instructions to Bears’ team captain Ray Olsen in 1936. Clarence “Nibs” Price retired from coaching Cal football and basketball in 1954. But he remained an avid follower of Cal sports, offering advice and support to his successors. In fact, it was Price who urged Cal to hire USF coach Pete Newell to succeed him as Cal’s basketball coach. Price died in Oakland on January 13, 1968. With his obituary on the front page of The Oakland Tribune, was a photograph of Price talking on the telephone. In a famous faux pas, the headline, written by a person who was unaware of what picture of Price was going to be used, proclaimed Death Calls Nibs Price. The good-natured Nibs Price would undoubtedly have been amused. The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U. Headquartered in Oakland, the system is composed of its ten campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Merced, Riverside, San Diego, San Francisco, Santa Barbara, and Santa Cruz, along with numerous research centers and academic abroad centers. [5] The system is the state’s land-grant university. [6] Major publications generally rank most UC campuses as being among the best universities in the world. In 1900, UC was one of the founders of the Association of American Universities and since the 1970s seven of its campuses, in addition to Berkeley, have been admitted to the association. Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, and San Diego are considered Public Ivies, making California the state with the most universities in the nation to hold the title. [7][8] UC campuses have large numbers of distinguished faculty in almost every academic discipline, with UC faculty and researchers having won 71 Nobel Prizes as of 2021. The system’s ten campuses have a combined student body of 295,573 students, 25,400 faculty members, 173,300 staff members and over two million living alumni. [2] Its newest campus in Merced opened in fall 2005. Nine campuses enroll both undergraduate and graduate students; one campus, UC San Francisco, enrolls only graduate and professional students in the medical and health sciences. In addition, the University of California College of the Law located in San Francisco is legally affiliated with UC and shares its name but is otherwise autonomous. Under the California Master Plan for Higher Education, the University of California is a part of the state’s three-system public higher education plan, which also includes the California State University system and the California Community Colleges system. UC is governed by a Board of Regents whose autonomy from the rest of the state government is protected by the state constitution. [10] The University of California also manages or co-manages three national laboratories for the U. Department of Energy: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), and Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL). The University of California was founded on March 23, 1868, and operated in Oakland, where it absorbed the assets of the College of California before moving to Berkeley in 1873. [12][13] It also affiliated with independent medical and law schools in San Francisco. Over the next eight decades, several branch locations and satellite programs were established across the state. In March 1951, the University of California began to reorganize itself into something distinct from its campus in Berkeley, with UC President Robert Gordon Sproul staying in place as chief executive of the UC system, while Clark Kerr became Berkeley’s first chancellor[14][15][16][17] and Raymond B. Allen became the first chancellor of UCLA. [18] However, the 1951 reorganization was stalled by resistance from Sproul and his allies, [19] and it was not until Kerr succeeded Sproul as UC president that UC was able to evolve into a university system from 1957 to 1960. [20] At that time, chancellors were appointed for additional campuses and each was granted some degree of greater autonomy. In November 1857, the College of California’s trustees began to acquire various parcels of land facing the Golden Gate in what is now Berkeley. In 1849, the state of California ratified its first constitution, which contained the express objective of creating a complete educational system including a state university. [22] Taking advantage of the Morrill Land-Grant Acts, the California State Legislature established an Agricultural, Mining, and Mechanical Arts College in 1866. [23][24] However, it existed only on paper, as a placeholder to secure federal land-grant funds. Meanwhile, Congregational minister Henry Durant, an alumnus of Yale, had established the private Contra Costa Academy, on June 20, 1853, in Oakland, California. [23] The initial site was bounded by Twelfth and Fourteenth Streets and Harrison and Franklin Streets in downtown Oakland[23] and is marked today by State Historical Plaque No. 45 at the northeast corner of Thirteenth and Franklin. In turn, the academy’s trustees were granted a charter in 1855 for a College of California, though the college continued to operate as a college preparatory school until it added college-level courses in 1860. [23][24] The college’s trustees, educators, and supporters believed in the importance of a liberal arts education (especially the study of the Greek and Roman classics), but ran into a lack of interest in liberal arts colleges on the American frontier (as a true college, the college was graduating only three or four students per year). South Hall, built in 1873, is the oldest building on the Berkeley campus. In November 1857, the college’s trustees began to acquire various parcels of land facing the Golden Gate in what is now Berkeley for a future planned campus to the north of Oakland. [23] But sales of new homesteads fell short. Governor Frederick Low favored the establishment of a state university based upon the University of Michigan plan, and thus in one sense may be regarded as the founder of the University of California. [23][24] At the College of California’s 1867 commencement exercises, where Low was present, Yale University professor Benjamin Silliman Jr. Criticized Californians for establishing a polytechnic school, instead of a real university. UC San Francisco campus in 1908. On October 9, 1867, the college’s trustees reluctantly agreed to join forces with the state college to their mutual advantage, but under one condition-that there not be simply an “Agricultural, Mining, and Mechanical Arts College”, but a complete university, within which the assets of the College of California would be used to create a College of Letters (now known as the College of Letters and Science). [23][24][26] Accordingly, the Organic Act, establishing the University of California, was introduced as a bill by Assemblyman John W. Dwinelle on March 5, 1868, and after it was duly passed by both houses of the state legislature, it was signed into state law by Governor Henry H. Haight (Low’s successor) on March 23, 1868. However, as legally constituted, the new university was not an actual merger of the two colleges, but was an entirely new institution which merely inherited certain objectives and assets from each of them. [28] Governor Haight saw no need to honor any tacit understandings reached with his predecessor about institutional continuity. [24] Only two college trustees became regents and a single faculty member (Martin Kellogg) was hired by the new university. [24] By April 1869, the trustees had second thoughts about their agreement to donate the college’s assets and disincorporate. To get them to proceed, regent John B. Felton helped them bring a “friendly suit” against the university to test the agreement’s legality-which they promptly lost. The University of California’s second president, Daniel Coit Gilman, opened its new campus in Berkeley in September 1873. The Citrus Experiment Station, built in 1917, is the oldest building on the UC Riverside campus. Section 8 of the Organic Act authorized the Board of Regents to affiliate the University of California with independent self-sustaining professional colleges. [31][32] “Affiliation” meant UC and its affiliates would “share the risk in launching new endeavors in education”. [31] It was through the process of affiliation that UC was able to claim it had medical and law schools in San Francisco within a decade of its founding. In 1879, California adopted its second and current constitution, which included unusually strong language to ensure UC’s independence from the rest of the state government. [10][33] This had lasting consequences for the Hastings College of the Law, which had been separately chartered and affiliated in 1878 by an act of the state legislature at the behest of founder Serranus Clinton Hastings. [34] After a falling out with his own handpicked board of directors, the founder persuaded the state legislature in 1883 and 1885 to pass new laws to place his law school under the direct control of the Board of Regents. [35] In 1886, the Supreme Court of California declared those newer acts to be unconstitutional because the clause protecting UC’s independence in the 1879 state constitution had stripped the state legislature of the ability to amend the 1878 act. [36][37] To this day, the College of the Law (which dropped Hastings from its name in 2023) remains a UC affiliate, maintains its own board of directors, and is not governed by the regents. Hart Hall at UC Davis, built in 1928, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. In contrast, Toland Medical College (founded in 1864 and affiliated in 1873) and later, the dental, pharmacy, and nursing schools in San Francisco were affiliated with UC through written agreements, and not statutes invested with constitutional importance by court decisions. [31] In the early 20th century, the Affiliated Colleges (as they came to be called) began to agree to submit to the regents’ governance during the term of President Benjamin Ide Wheeler, as the Board of Regents had come to recognize the problems inherent in the existence of independent entities that shared the UC brand but over which UC had no real control. [31] While Hastings remained independent, the Affiliated Colleges were able to increasingly coordinate their operations with one another under the supervision of the UC president and regents, and evolved into the health sciences campus known today as the University of California, San Francisco. North-south tensions and decentralization. Powell Library, built in 1929, is one of the four oldest buildings on the UCLA campus. In August 1882, the California State Normal School (whose original normal school in San Jose is now San Jose State University) opened a second school in Los Angeles to train teachers for the growing population of Southern California. [38] In 1887, the Los Angeles school was granted its own board of trustees independent of the San Jose school, and in 1919, the state legislature transferred it to UC control and renamed it the Southern Branch of the University of California. [39] In 1927, it became the University of California at Los Angeles; the “at” would be replaced with a comma in 1958. Los Angeles surpassed San Francisco in the 1920 census to become the most populous metropolis in California. Their efforts bore fruit in March 1951, when UCLA became the first UC site outside of Berkeley to achieve de jure coequal status with the Berkeley campus. That month, the regents approved a reorganization plan under which both the Berkeley and Los Angeles campuses would be supervised by chancellors reporting to the UC president. [14][15][16][41] However, the 1951 plan was severely flawed; it was overly vague about how the chancellors were to become the “executive heads” of their campuses. Due to stubborn resistance from President Sproul and several vice presidents and deans-who simply carried on as before-the chancellors ended up as glorified provosts with limited control over academic affairs and long-range planning while the president and the regents retained de facto control over everything else. UC Irvine was founded and had its campus built out in the 1960s. Upon becoming president in October 1957, Clark Kerr supervised UC’s rapid transformation into a true public university system through a series of proposals adopted unanimously by the regents from 1957 to 1960. [20][21] Kerr’s reforms included expressly granting all campus chancellors the full range of executive powers, privileges, and responsibilities which Sproul had denied to Kerr himself, as well as the radical decentralization of a tightly knit bureaucracy in which all lines of authority had always run directly to the president at Berkeley or to the regents themselves. [20][21][41] In 1965, UCLA Chancellor Franklin D. Murphy tried to push this to what he saw as its logical conclusion: he advocated for authorizing all chancellors to report directly to the Board of Regents, thereby rendering the UC president redundant. [42] Murphy wanted to transform UC from one federated university into a confederation of independent universities, similar to the situation in Kansas (from where he was recruited). [42] Murphy was unable to develop any support for his proposal, Kerr quickly put down what he thought of as “Murphy’s rebellion”, and therefore Kerr’s vision of UC as a university system prevailed: “one university with pluralistic decision-making”. Geisel Library, at UC San Diego, was built in 1970. During the 20th century, UC acquired additional satellite locations which, like Los Angeles, were all subordinate to administrators at the Berkeley campus. California farmers lobbied for UC to perform applied research responsive to their immediate needs; in 1905, the Legislature established a “University Farm School” at Davis and in 1907 a “Citrus Experiment Station” at Riverside as adjuncts to the College of Agriculture at Berkeley. In 1912, UC acquired a private oceanography laboratory in San Diego, which had been founded nine years earlier by local business promoters working with a Berkeley professor. In 1944, UC acquired Santa Barbara State College from the California State Colleges, the descendants of the State Normal Schools. [43] In 1958, the regents began promoting these locations to general campuses, thereby creating UCSB (1958), UC Davis (1959), UC Riverside (1959), UC San Diego (1960), and UCSF (1964). [44][45] Each campus was also granted the right to have its own chancellor upon promotion. In response to California’s continued population growth, UC opened two additional general campuses in 1965, with UC Irvine opening in Irvine and UC Santa Cruz opening in Santa Cruz. [44] The youngest campus, UC Merced opened in fall 2005 to serve the San Joaquin Valley. UC Santa Cruz, founded in 1965. After losing campuses in Los Angeles and Santa Barbara to the University of California system, supporters of the California State College system arranged for the state constitution to be amended in 1946 to prevent similar losses from happening again in the future. With decentralization complete, it was decided in 1986 that the UC president should no longer be based at the Berkeley campus, and the UC Office of the President moved to Kaiser Center in Oakland in 1989. [46] That lakefront location was subject to widespread criticism as “too elegant and too corporate for a public university”. [47] In 1998, the Office of the President moved again, to a newly constructed but much more modest building near the former site of the College of California in Oakland. UC Merced, founded in 2005. The California Master Plan for Higher Education of 1960 established that UC must admit undergraduates from the top 12.5% (one-eighth) of graduating high school seniors in California. Prior to the promulgation of the Master Plan, UC was to admit undergraduates from the top 15%. UC does not currently adhere to all tenets of the original Master Plan, such as the directives that no campus was to exceed total enrollment of 27,500 students (in order to ensure quality) and that public higher education should be tuition-free for California residents. Five campuses, Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, and San Diego, each have current total enrollment at over 30,000, and of these five, all but Irvine have undergraduate enrollments over 30,000. [52] As part of its search for funds during the 2000s and 2010s, UC quietly began to admit higher percentages of highly accomplished (and more lucrative) students from other states and countries, [53] but was forced to reverse course in 2015 in response to the inevitable public outcry and start admitting more California residents. On November 14, 2022, about 48,000 academic workers at all regent-governed UC campuses, as well as the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, went on strike for higher pay and benefits as authorized by the United Auto Workers (UAW) union. [56] UAW has cited more than 20 unfair labor practice charges performed by UC, including unilateral changes in policy and obstructing worker negotiation. [57] The strike lasted almost six weeks, officially ending on December 23. Office of the President of the University of California, in Oakland. All University of California campuses except the College of the Law in San Francisco are governed by the Regents of the University of California as required by the Constitution of the State of California. [33] Eighteen regents are appointed by the governor for 12-year terms. [33] One member is a student appointed for a one-year term. [33] There are also seven ex officio members-the governor, lieutenant governor, speaker of the State Assembly, State Superintendent of Public Instruction, president and vice president of the UC alumni associations, and the UC president. [33] The Academic Senate, made up of faculty members, is empowered by the regents to set academic policies. [33] In addition, the system-wide faculty chair and vice-chair sit on the Board of Regents as non-voting members. President of the University of California. Blake House and Gardens, built by architect Walter Danforth Bliss in 1924, served as the official residence of the UC President, from 1967 until 2008, when it was opened to the public. Originally, the president was the chief executive of the first campus, Berkeley. In turn, other UC locations (with the exception of the Hastings College of the Law) were treated as off-site departments of the Berkeley campus, and were headed by provosts who were subordinate to the president. In March 1951, the regents reorganized the university’s governing structure. Starting with the 1952-53 academic year, day-to-day “chief executive officer” functions for the Berkeley and Los Angeles campuses were transferred to chancellors who were vested with a high degree of autonomy, and reported as equals to UC’s president. [14][15][16] As noted above, the regents promoted five additional UC locations to campuses and allowed them to have chancellors of their own in a series of decisions from 1958 to 1964, [44] and the three campuses added since then have also been run by chancellors. In turn, all chancellors (again, with the exception of Hastings) report as equals to the University of California President. Today, the UC Office of the President (UCOP) and the Office of the Secretary and Chief of Staff to the Regents of the University of California share an office building in downtown Oakland that serves as the UC system’s headquarters. Kerr’s vision for UC governance was “one university with pluralistic decision-making”. [60] In other words, the internal delegation of operational authority to chancellors at the campus level and allowing nine other campuses to become separate centers of academic life independent of Berkeley did not change the fact that all campuses remain part of one legal entity. As a 1968 UC centennial coffee table book explained: Yet for all its campuses, colleges, schools, institutes, and research stations, it remains one University, under one Board of Regents and one president-the University of California. “[61] UC continues to take a “united approach as one university in matters in which it inures to UC’s advantage to do so, such as when negotiating with the legislature and governor in Sacramento. [60] The University of California continues to manage certain matters at the systemwide level in order to maintain common standards across all campuses, such as student admissions, appointment and promotion of faculty, and approval of academic programs. Drake, 21st President of the University of California (2020-present). All UC presidents had been white men until 2013, when former Homeland Security Secretary, and Governor of Arizona, Janet Napolitano became the first woman to hold the office of UC President. [63] On July 7, 2020, Dr. Drake, a former UC chancellor and medical research professor, was selected as the 21st president of the University of California system, making him the first black president to hold the office in UC’s 152-year history. He took office on August 1, 2020. University House, Berkeley served as the official residence of the UC President from 1911 until 1958. Today it serves Berkeley’s Chancellor. Besides substantial six-figure incomes, the UC president and all UC chancellors enjoy controversial perks such as free housing in the form of university-maintained mansions. [65] In 1962, Anson Blake’s will donated his 10-acre (40,000 m2) estate (Blake Garden) and mansion (Blake House) in Kensington to the University of California’s Department of Landscape Architecture. In 1968, the regents decided to make Blake House the official residence of the UC president. [66] From 2008 to 2022, all three UC presidents during that timeframe i. Yudof, Napolitano, and Drake lived in rented homes. [66] UC had previously owned the same home from 1971 to 1991, when it served as the official residence of the UC vice president. [66] UC no longer has a single “vice president”; the president’s direct reports now have titles like “executive vice president”, “senior vice president”, or “vice president”. Selden Williams House, built in 1928 and designed by architect Julia Morgan, serves as the official residence of the UC President, since 2022. All UC chancellors traditionally live for free in a mansion on or near campus that is usually known as University House, where they host social functions attended by guests and donors. [68] Berkeley’s University House formerly served as the official residence of the UC president, but is now the official residence of Berkeley’s chancellor. [69][70] Not all chancellors prefer to live on campus; at Santa Barbara, Chancellor Robert Huttenback found that campus’s University House to be unsatisfactory, then was convicted in 1988 of embezzlement for his unauthorized use of university funds to improve his off-campus residence. Main article: University of California finances. The “UC Budget for Current Operations” lists the medical centers as the largest revenue source, contributing 39% of the budget, the federal government 11%, Core Funds (State General Funds, UC General Funds, student tuition) 21%, private support (gifts, grants, endowments) 7%, and Sales and Services at 21%. In 1980, the state funded 86.8% of the UC budget. [72] While state funding has somewhat recovered, as of 2019 state support still lags behind even recent historic levels e. 2001 when adjusted for inflation. According to the California Public Policy Institute, California spends 12% of its General Fund on higher education, but that percentage is divided between the University of California, California State University and California Community Colleges. View of the UC Office of the President. In May 2004, UC President Robert C. Dynes and CSU Chancellor Charles B. Reed struck a private deal, called the “Higher Education Compact”, with Governor Schwarzenegger. In 2008, the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, the regional accreditor of the UC schools, criticized the UC system for “significant problems in governance, leadership and decision making” and “confusion about the roles and responsibilities of the university president, the regents and the 10 campus chancellors with no clear lines of authority and boundaries”. In 2016, university system officials admitted that they monitored all e-mails sent to and from their servers. A topographic map of California with the UC campuses markedBerkeleyBerkeleySan DiegoSan DiegoLos AngelesLos AngelesSanta BarbaraSanta BarbaraSan FranciscoSan FranciscoIrvineIrvineDavisDavisSanta CruzSanta CruzRiversideRiversideMercedMerced. The ten UC campuses. At present, the UC system officially describes itself as a “ten campus” system consisting of the campuses listed below. [82] These campuses are under the direct control of the regents and president. [83] Only ten campuses are listed on the official UC letterhead. Although it shares the name and public status of the UC system, the College of the Law, San Francisco (formerly Hastings College of the Law) is not controlled by the regents or president; it has a separate board of directors and must seek funding directly from the Legislature. However, under the California Education Code, Hastings degrees are awarded in the name of the regents and bear the signature of the UC president. [85] Furthermore, Education Code section 92201 states that Hastings “is affiliated with the University of California, and is the law department thereof”. Annually, UC campuses are ranked highly by various publications. Six UC campuses rank in the top 50 U. National Universities of 2022 by U. News & World Report, with UCLA, Berkeley, UC Santa Barbara, UC San Diego, UC Irvine, and UC Davis all ranked in the top 50. Four UC campuses also ranked in the top 50 in the U. News & World Report Best Global Universities Rankings in 2021, namely Berkeley, UCLA, UCSF, and UC San Diego. [87] UCSF is ranked as one of the top universities in biomedicine in the world[88][89][90][91][92][93] and the UCSF School of Medicine is ranked 3rd in the United States among research-oriented medical schools and for primary care by U. News & World Report. Three UC campuses: Berkeley, UCLA, and UC San Diego all ranked in the top 15 universities in the US according to the 2020 Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) US National University Rankings and also in the top 20 in World University Rankings. The Academic Ranking of World Universities also ranked UCSF, UC Davis, UC Irvine, and UC Santa Barbara in the top 50 US National Universities and in the top 100 World Universities in 2020. Berkeley, UCLA, and UC San Diego all ranked in the top 50 universities in the world according to both the Times Higher Education World University Rankings for 2021 and the Center for World University Rankings (CWUR) for 2020, while UC Irvine, UC Santa Barbara, and UC Davis ranked in the top 100 universities in the world. [96][97] Forbes also ranked the six UC campuses mentioned above as being in the top 50 universities in America in 2021. [98] Forbes also named the top three public universities in America as all being UC campuses, namely, Berkeley, UCLA, and UCSD, and ranked three more campuses, UC Davis, UC Santa Barbara, and UC Irvine as being among the top 20 public universities in America in 2021. [99] The six aforementioned campuses are all considered Public Ivies. [7] The QS World University Rankings for 2021 ranked three UC campuses: Berkeley, UCLA and UC San Diego as being in the top 100 universities in the world. Individual academic departments also rank highly among the UC campuses. News & World Report Best Graduate Schools report ranked Berkeley as being among the top 5 universities in the nation in the departments of Psychology, Economics, Political Science, Computer Science, Engineering, Biological Sciences, Chemistry, Mathematics, Earth Sciences, Physics, Sociology, History, and English, and ranked UCLA in the top 20 in the same departments. News & World Report also ranked the same departments at UC San Diego among the top 20 in the nation, with the exception of the departments of Sociology, History, and English. [103] UC Davis, UC Irvine and UC Santa Barbara ranked in the top 50 in the departments of Psychology, Economics, Political Science, Computer Science, Engineering, Biological Sciences, Chemistry, Mathematics, Earth Sciences, Physics, Sociology, History, and English, with the exception of UC Santa Barbara’s Psychology and Political Science departments, according to U. UC Santa Cruz and UC Riverside ranked in the top 100 in the nation in the same departments, along with UC Merced’s Psychology and Political Science departments. News & World Report National Ranking. News & World Report World Ranking. THE World University Rankings. QS World University Rankings. Pac-12 (ACC in 2024). Pac-12 (Big Ten in 2024). CalPac (NCAA D-II CCAA in 2024). Doe Memorial Library, main facility of the UC Berkeley Libraries. Langson Library at UC Irvine. As of the end of fiscal year 2022, UC controls 13,702 active patents. UC researchers and faculty were responsible for 1,570 new inventions that same year. [2] On average, UC researchers create four new inventions per day. Eight of UC’s ten campuses (Berkeley, UC Davis, UCI, UCLA, UC Riverside, UCSD, UC Santa Barbara, and UC Santa Cruz) are members of the Association of American Universities (AAU), [2] an alliance of elite American research universities[110] founded in 1900 at UC’s suggestion. [111] Collectively, the system counts among its faculty (as of 2002). 389 members of the Academy of Arts and Sciences. 5 Fields Medal recipients. 254 members of the National Academy of Sciences. 91 members of the National Academy of Engineering. 13 National Medal of Science laureates. 61 Nobel laureates[9]. 106 members of the Institute of Medicine. Powell Library, main facility of the UCLA Library. Kolligian Library at UC Merced. As of October 2021, the following data are taken from List of Nobel laureates by university affiliation, which counts university alumni and staff, and are not the official count from the University of California. 10 years of age. Main article: University of California Libraries. Davidson Library, the main facility of the UC Santa Barbara Library. At 40.8 million print volumes, [112] the University of California library system is home to one of the largest collections of printed materials in the world. On July 27, 2021, all ten campuses went live with a unified online library catalog, UC Library Search. Besides on-campus libraries, the UC system also maintains two regional library facilities (one each for Northern and Southern California), which each accept older items from all UC campus libraries in their respective region. As of 2019, Northern Regional Library Facility is home to 7.4 million items, while Southern Regional Library Facility is home to 6.5 million items. Eight campuses operate on the quarter system, while two (Berkeley and Merced) are on the semester system. However, all five law schools operate on the semester system, as does the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. McHenry Library at UC Santa Cruz. Davis, Los Angeles, Riverside, and Santa Barbara all followed Berkeley’s example by aggregating the majority of arts, humanities, and science departments into a relatively large College of Letters and Science. Therefore, at Berkeley, Davis, Los Angeles, and Santa Barbara, their respective College of Letters and Science is by far the single largest academic unit on each campus. The College of Letters and Science at Los Angeles is the largest academic unit in the entire UC system. [113] Riverside later separated the natural sciences and kept only social sciences grouped with arts and humanities, an example followed by Merced at its founding. Due to President Kerr’s interest in not reproducing the impersonal undergraduate experience often seen in such gigantic academic units, San Diego and Santa Cruz both implemented residential college systems inspired by British models (in which each college has distinctive general education requirements reflecting its chosen theme)[114] and grouped most academic departments into a small number of broadly defined divisions which are all independent of the colleges. Finally, Irvine is organized into 13 schools and San Francisco is organized into four schools, all of which are relatively narrow in scope. Kerckhoff Hall is home of the Associated Students of the University of California, Los Angeles. Each UC campus handles admissions separately, but a student wishing to apply for an undergraduate or transfer admission uses one application for all UC campuses. Graduate and professional school admissions are handled directly and separately by each department or program to which one applies. In May 2020, UC approved plans to suspend standardized testing score requirements in admissions until 2024. [115] In May 2021, after a student lawsuit, the University of California announced that it would no longer consider SAT and ACT scores in admissions and scholarship decisions. The Early Academic Outreach Program (EAOP) was established in 1976 by University of California (UC) in response to the State Legislature’s recommendation to expand post-secondary opportunities to all of California’s students including those who are first-generation, socioeconomically disadvantaged, and English-language learners. [117] As UC’s largest academic preparation program, EAOP assists middle and high school students with academic preparation, admissions requirements, and financial aid requirements for higher education. [118] The program designs and provides services to foster students’ academic development, and delivers those services in partnership with other academic preparation programs, schools, other higher education institutions and community/industry partners. Haas School of Business at Berkeley is ranked among the best business schools in the world. The University of California admits a significant number of transfer students primarily from the California Community Colleges. [120] Approximately one out of three UC students begin at a community college before graduating. [120] In evaluating a transfer student’s application the universities conduct a “comprehensive review” process that includes consideration of grade point averages of the generally required, transferable and or related courses for the intended major. The review may also include consideration of an applicant’s enrollment in selective honor courses or programs, extracurricular activities, essay, family history, life challenges, and the location of the student’s residence. Different universities emphasize different factors in their evaluations. Before 1986, students who wanted to apply to UC for undergraduate study could only apply to one campus. Students who were rejected at that campus but otherwise met the UC minimum eligibility requirements were redirected to another campus with available space. [citation needed] UC Riverside chancellor Ivan Hinderaker explained in 1972: Redirection has been a negative rather than a plus. Some come with a chip on their shoulders so big they never give the campus a chance. They poison the attitudes of the students around them. Jacobs School of Engineering, at San Diego, is one of the top-ranked engineering schools in the country. This significantly increased the number of applications to the Berkeley and Los Angeles campuses, since students could choose a campus to attend after they received acceptance letters, without fear of being redirected to a campus they did not want to attend. The University of California accepts fully eligible students from among the top one-eighth (1/8) of California public high school graduates through regular statewide admission, or the top 9% of any given high school class through Eligibility in the Local Context (see below). Part of the eligibility process is completion of the A-G requirements in high school. All eligible California high school students who apply are accepted to the university, though not necessarily to the campus of choice. [124][125] Eligible students who are not accepted to the campus(es) of their choice are placed in the “referral pool”, where campuses with open space may offer admission to those students; in 2003, 10% of students who received an offer through this referral process accepted it. [126] In 2007, about 4,100 UC-eligible students who were not offered admission to their campus of choice were referred to UC Riverside or the system’s newest campus, UC Merced. [127] In 2015, all UC-eligible students rejected by their campus of choice were redirected to UC Merced, which is now the only campus that has space for all qualified applicants. UCLA School of Law is one of the top ranked law schools in the United States. The old undergraduate admissions were conducted on a two-phase basis. In the first phase, students were admitted based solely on academic achievement. This accounted for between 50 and 75% of the admissions. In the second phase, the university conducted a “comprehensive review” of the student’s achievements, including extracurricular activities, essay, family history, and life challenges, to admit the remainder. Students who did not qualify for regular admission were “admitted by exception”; in 2002, approximately 2% of newly admitted undergraduates were admitted by exception. The process for determining admissions varies. At some campuses, such as Santa Barbara and Santa Cruz, a point system is used to weight grade point average, SAT Reasoning or ACT scores, and SAT Subject scores, while at San Diego, Berkeley, and Los Angeles, academic achievement is examined in the context of the school and the surrounding community, known as a holistic review. Race, gender, national origin, and ethnicity were not used as UC admission criteria due to the passing of Proposition 209. This information was collected for statistical purposes. Eligibility in the Local Context, commonly referred to as ELC, is met by applicants ranked in the top 9% of their high school class in terms of performance on an 11-unit pattern of UC-approved high school courses. Beginning with fall 2007 applicants, ELC also requires a UC-calculated GPA of at least 3.0. Fully eligible ELC students are guaranteed a spot at one of UC’s undergraduate campuses, though not necessarily at their first-choice campus or even to a campus to which they applied. In 2021, the University of California freshmen class was its most diverse and largest ever, with 84,223 students. [130] Latinos were the largest group at 37%; Asian Americans at 34%; white non-Hispanics at 20%; African-Americans at 5%; and 4% composed of American Indians, Pacific Islanders or those who declined to state their race or ethnicity. Percentage of students and comparisons statewide-nationwide. Hispanic/Latino(a) (of any race; including Chicanos and White Hispanics). Mrak Hall serves as the administrative seat of UC Davis. In many recent years, the University of California has faced growing criticism for high admissions of out-of-state or international students as opposed to in-state, California students. In particular, UC Berkeley and UCLA have been heavily criticized for this phenomenon due to their extraordinarily low acceptance rates compared to other campuses in the system. [134] At a Board of Regents meeting in 2015, California Governor Jerry Brown reportedly said about the problem: And so you got your foreign students and you got your 4.0 folks, but just the kind of ordinary, normal students, you know, that got good grades but weren’t at the top of the heap there-they’re getting frozen out. [135] State lawmakers have proposed legislation that would reduce out-of-state admission. A 2020 California auditor’s report indicated that at least 64 wealthy students were wrongfully admitted to UC schools as favors to powerful figures. [137][138][139] Many of the admissions were justified by falsely classifying the applicants as student athletes. The incidents disproportionately (55 of 64) occurred at UC Berkeley. The California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology, jointly run by UC San Diego, UC Irvine, and UC Riverside. In 2006 the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC) awarded the University of California the SPARC Innovator Award for its “extraordinarily effective institution-wide vision and efforts to move scholarly communication forward”, including the 1997 founding under then UC President Richard C. Atkinson of the California Digital Library (CDL) and its 2002 launching of CDL’s eScholarship, an institutional repository. On July 24, 2013, the UC Academic Senate adopted an Open Access Policy, mandating that all UC faculty produced research with a publication agreement signed after that date be first deposited in UC’s eScholarship open access repository. University of California systemwide research on the SAT exam found that, after controlling for familial income and parental education, so-called achievement tests known as the SAT II had 10 times more predictive ability of college aptitude than the SAT I. One of their faculty members, Dr. Mitloehner, and a former student, Dr. The University of California has a long tradition of involvement in many enterprises that are often geographically or organizationally separate from its general campuses, including national laboratories, observatories, hospitals, continuing education programs, hotels, conference centers, an airport, a seaport, and an art institute. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the Berkeley Hills. The University of California directly manages and operates one United States Department of Energy National Laboratory:[144]. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL, or Berkeley Lab) (Berkeley, California). UC is a limited partner in two separate private limited liability companies that manage and operate two other Department of Energy national laboratories. Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) (Los Alamos, New Mexico) operated by Triad National Security, LLC. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) (Livermore, California) operated by Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory staff on the magnet yoke for the 60-inch cyclotron, 1938; Nobel prize winners Ernest Lawrence, Edwin McMillan, and Luis Alvarez are shown, in addition to J. Robert Oppenheimer and Robert R. The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory conducts unclassified research across a wide range of scientific disciplines with key efforts focused on fundamental studies of the universe, quantitative biology, nanoscience, new energy systems and environmental solutions, and the use of integrated computing as a tool for discovery. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in the Livermore Valley. The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory uses advanced science and technology to ensure that U. Nuclear weapons remain reliable. LLNL also has major research programs in supercomputing and predictive modeling, energy and environment, bioscience and biotechnology, basic science and applied technology, counter-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and homeland security. It is also home to the most powerful supercomputers in the world. The Los Alamos National Laboratory focuses most of its work on ensuring the reliability of U. Other work at LANL involves research programs into preventing the spread of weapons of mass destruction and US national security, such as protection of the US homeland from terrorist attacks. The UC system’s ties to the three laboratories have occasionally sparked controversy and protest, because all three laboratories have been intimately linked with the development of nuclear weapons. During the World War II Manhattan Project, Lawrence Berkeley Lab developed the electromagnetic method for the separation of uranium isotopes used to develop the first atomic bombs. The Los Alamos and Lawrence Livermore labs have been involved in designing U. Nuclear weapons from their inception until the shift into stockpile stewardship after the end of the Cold War. Historically the two national laboratories in Berkeley and Livermore named after Ernest O. Lawrence, have had very close relationships on research projects, as well as sharing some business operations and staff. In fact, LLNL was not officially severed administratively from LBNL until the early 1970s. They also have much deeper ties to the university than the Los Alamos Lab, a fact seen in their respective original names; the University of California Berkeley Radiation Laboratory and the University of California Radiation Laboratory at Livermore. Lick Observatory, atop Mount Hamilton in the Diablo Range. The UC system’s ties to the labs have so far outlasted all periods of internal controversy. However, in 2003, the U. UC entered into a partnership with Bechtel Corporation, BWXT, and the Washington Group International, and together they created a private company called Los Alamos National Security, LLC (LANS). In December 2005, a seven-year contract to manage the laboratory was awarded to the Los Alamos National Security, LLC. [145] On October 1, 2007, the University of California ended its direct involvement in operating the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Management of the laboratory was taken over by Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, a limited liability company whose members are Bechtel National, the University of California, Babcock & Wilcox, the Washington Division of URS Corporation, Battelle Memorial Institute, and The Texas A&M University System. Other than UC appointing three members to the two separate boards of directors (each with eleven members) that oversee LANS and LLNS, UC now has virtually no responsibility for or direct involvement in either LANL or LLNL. UC policies and regulations that apply to UC campuses and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California no longer apply to LANL and LLNL, and the LANL and LLNL directors no longer report to the UC Regents or UC Office of the President. The University of California manages two observatories as a multi-campus research unit headquartered at UC Santa Cruz. Lick Observatory atop Mount Hamilton, in the Diablo Range just east of San Jose. The Astronomy Department at the Berkeley campus manages the Hat Creek Radio Observatory in Shasta County. The University of California is a founding and charter member of the Corporation for Education Network Initiatives in California, a nonprofit organization that provides high-performance Internet-based networking to California’s K-20 research and education community. UC Natural Reserve System. Main article: University of California Natural Reserve System. The NRS was established in January 1965 to provide UC faculty with large areas of land where they could conduct long-term ecosystem research without having to worry about outside disturbances like tourists. Today, the NRS manages 39 reserves that total more than 756,000 acres (3,060 km2). Selected reserves of the University of California Natural Reserve System. Coal Oil Point Reserve. Stebbins Cold Canyon Reserve. UC Agriculture and Natural Resources. University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources[146] (UCANR, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources) plays an important role in the state’s agriculture industry, as mandated by UC’s legacy as a land-grant institution. In addition to conducting agriculture and Youth development research, every county in the state has a cooperative extension office with county farm advisors. The county offices also support 4-H programs and have nutrition, family, and consumer sciences advisors who assist local government. Currently, the division’s University of California 4-H Youth Development Program[147] is a national leader in studying thriving in the field of youth development. Other national research centers. UC Santa Cruz managed the UARC for the University of California, with the goal of increasing the science output, safety, and effectiveness of NASA’s missions through new technologies and scientific techniques. Since 2002, the NSF-funded San Diego Supercomputer Center at UC San Diego has been managed by the University of California, which took over from the previous manager, General Atomics. Medical centers and schools. UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital. The University of California operates five medical centers throughout the state. UC Davis Medical Center, in Sacramento. UC Irvine Medical Center, in Orange. UCLA Medical Center, comprising two distinct hospitals. Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, in Los Angeles. UCLA Santa Monica Medical Center, in Santa Monica. UC San Diego Medical Center, comprising two distinct hospitals. UC San Diego Medical Center, Hillcrest, in San Diego. Jacobs Medical Center, in La Jolla; and. UCSF Medical Center, operating as a single medical center across three physically distinct campuses around San Francisco. Medical centers of the University of California. There are two medical centers that bear the UCLA name, but are not operated by UCLA: Harbor-UCLA Medical Center and Olive View-UCLA Medical Center. They are actually Los Angeles County-operated facilities that UCLA uses as teaching hospitals. UCLA Mattel Children’s Hospital. Each medical center serves as the primary teaching site for that campus’s medical school. UCSF is perennially among the top five programs in both research and primary care, and both UCLA and UC San Diego consistently rank among the top fifteen research schools, according to annual rankings published by U. [149] The teaching hospitals affiliated with each school are also highly regarded – the UCSF Medical Center was ranked the number one hospital in California and number 5 in the country by U. News & World Report’s 2017 Honor Roll for Best Hospitals in the United States. [150] UC also has a sixth medical school-UC Riverside School of Medicine, the only one in the UC system without its own hospital. In the latter half of the 20th century, the UC hospitals became the cores of full-fledged regional health systems; they were gradually supplemented by many outpatient clinics, offices, and institutes. The medical hospitals operated by UC Irvine (acquired in 1976), UC Davis (acquired in 1978), and UC San Diego (acquired in 1984) each began as the respective county hospitals of Orange County, Sacramento County, and San Diego County. As of 2024, UC medical centers handle each year about 10 million outpatient visits, 393,802 emergency room visits, and roughly 1.23 million inpatient days. Facilities outside of California. Casa de California in Mexico City. UC operates several other miscellaneous sites to support faculty, students, and researchers away from its general campuses. The UC Office of the President’s Education Abroad Program currently operates one mini-campus which supports UC students, faculty, and alumni overseas. EAP also briefly operated California House in London during the early-to-mid 2000s. UC Washington Center in Washington, D. With a dormitory for students interning with the federal government. UC Davis’s UC Center Sacramento supports students interning with the California government. UC Berkeley operates the Richard B. Gump South Pacific Research Station in Mo’orea, French Polynesia on land donated in 1981 by the heir to the founder of the Gump’s home furnishings store. Scripps Institution of Oceanography pier, in La Jolla. Unlike other land-grant institutions e. Cornell UC does not provide a hospitality management program, but it does provide general hospitality at some locations. UC Berkeley’s Cal Alumni Association operates travel excursions for alumni (and their families) under its “Cal Discoveries Travel” brand (formerly BearTreks); many of the tour guides are Berkeley professors. CAA also operates the oldest and largest alumni association-run family camp in the world, the Lair of the Golden Bear. Located at an altitude of 5600 feet in Pinecrest, California, the Lair is a home-away-from-home for almost 10,000 campers annually. Its attendees are largely Cal alumni and their families, but the Lair is open to everyone. Berkeley Lab operates its own hotel, the Berkeley Lab Guest House, available to persons with business at the Lab itself or UC Berkeley. UCLA Housing & Hospitality Services operates two on-campus hotels, the 61-room Guest House and the 254-room Meyer & Renee Luskin Conference Center, and a lavish off-campus conference center at Lake Arrowhead (with a mix of chalet-like condominiums, lodge rooms, and stand-alone cottages). During the summer, the Lake Arrowhead conference center hosts the Bruin Woods vacation programs for UCLA alumni and their families. Separately, UCLA Health operates the 100-room Tiverton House just south of the UCLA campus to serve its patients and their families. UC Santa Cruz leased the University Inn and Conference Center in downtown Santa Cruz from 2001 to 2011 for use as off-campus student housing. University of California Museum of Paleontology in Berkeley. UC Davis operates the University Airport as a utility airport for air shuttle service in the contractual transportation of university employees and agricultural samples. It is also a public general aviation airport. University Airport’s ICAO identifier is KEDU. UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography owns a seaport, the Nimitz Marine Facility, which is just south of Shelter Island on Point Loma, San Diego. The port is used as an operating base for all of its oceanographic vessels and platforms. For over a century, the university has operated a continuing education program for working adults and professionals. At present, UC Extension enrolls over 500,000 students each year in over 17,000 courses. One of the reasons for its large size is that UC Extension is a dominant provider of Continuing Legal Education and Continuing Medical Education in California. For example, the systemwide portion of UC Extension (directly controlled by the UC Office of the President) operates Continuing Education of the Bar under a joint venture agreement with the State Bar of California. San Francisco Bay Area portal. Police departments at the University of California. University of California Press. University of California Student Association.