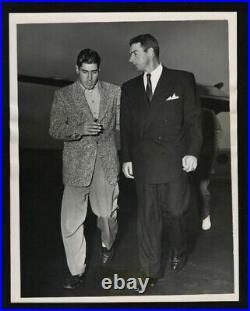

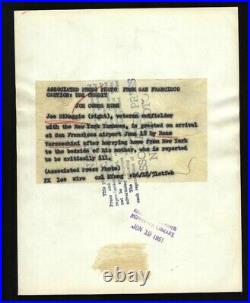

A VINTAGE ORIGINAL APPROXIAMTELY 7 1/8 X 9 INCH PHOTOGRAPH OF JOE DIMAGGIO FROM 1951. Joe DiMaggio was a cultural icon. He married Hollywood starlets Marilyn Monroe and Dorothy Arnold and he was immortalized in Paul Simon’s hit song Mrs. Robinson; to a generation he was the face of Mister Coffee, and he was regarded as one of the greatest players who ever played the game. He was an American hero. Hall of Fame teammate Phil Rizzuto recalled: There was an aura about him. He walked like no one else walked. He did things so easily. He was immaculate in everything he did. Kings of State wanted to meet him and be with him. He carried himself so well. He could fit in any place in the world. On the ball field Joe DiMaggio could do it all. Hall of Famer owner and manager Connie Mack called him “the best player that ever lived”, and longtime teammate Yogi Berra said: I wish everybody had the drive he had. He never did anything wrong on the field. I’d never seen him dive for a ball, everything was a chest-high catch, and he never walked off the field. The son of a San Francisco fisherman, Joe was the eighth of nine children – and his brothers Vince and Dom were also Major League All-Stars. Of his on field accomplishments, perhaps none are more notable than his 56-game hitting streak in 1941. However, that streak was not the longest of his professional career. In 1933, as a member of the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League, DiMaggio put together a 61-game hitting streak. By the 1970s, broadcasters and writers began simply to call him Joe D. And because he was so ingrained in American culture, everyone knew who they were talking about. His rival Ted Williams said: DiMaggio was the greatest all-around player I ever saw. His career cannot be summed up in numbers and awards. It might sound corny, but he had a profound and lasting impact on the country. His successor in center field at Yankee Stadium Mickey Mantle described how he viewed the Yankee Clipper: Heroes are people who are all good with no bad in them. That’s the way I always saw Joe DiMaggio. He was beyond question one of the greatest players of the century. DiMaggio was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1955. He passed away on March 8, 1999. Joe DiMaggio, byname of Joseph Paul DiMaggio, also called Joltin’ Joe or the Yankee Clipper, born November 25, 1914, Martinez, California, U. Died March 8, 1999, Hollywood, Florida, American professional baseball player who was an outstanding hitter and fielder and one of the best all-around players in the history of the game. DiMaggio was the son of Italian immigrants who made their living by fishing. He quit school at 14 and at 17 joined his brother Vincent and began playing baseball with the minor league San Francisco Seals. In addition to Vincent, who would go on to play for several major league teams, including the Pittsburgh Pirates, a younger DiMaggio brother, Dominic, played for the Boston Red Sox. In his rookie season with the Yankees he batted. 323 during the regular season and. 346 against the New York Giants during the World Series. In 1937 DiMaggio led the American League in home runs and runs scored, and in 1939 and 1940 he led the American League in batting, with averages of. DiMaggio was a very consistent hitter; early in his career, during his 1933 season with the Seals, he had a hitting streak of 61 consecutive games. His consistency led to one of the most remarkable records of major league baseball-DiMaggio’s feat of hitting safely in 56 consecutive games (May 15-July 16, 1941). The prior record for the longest hitting streak of 44 games was set in 1897 (and, at that time, foul balls did not count as strikes). With the exception of DiMaggio’s streak, no player has hit in more than 44 consecutive games since. In addition to his fine hitting ability, DiMaggio had outstanding skill as a fielder, tying the American League fielding record in 1947 with only one error in 141 games. Indeed, he played his position in center field with such languid expertise that some ill-informed fans thought he was lazy-he rarely had to jump against the outfield wall to make a catch or dive for balls, he was simply there to catch them. Between 1936 and 1951 DiMaggio helped the Yankees to nine World Series titles-in 1936, 1937, 1938, 1939, 1941, 1947, 1949, 1950, and 1951. During the same period the Yankees won 10 American League championships the Yankees won the pennant but not the World Series in 1942. DiMaggio missed three seasons (1943 through 1945) serving in the military during World War II. Joe DiMaggio about to kiss his baseball bat, 1941. The Sporting News Pub. /Library of Congress, Washington, D. Get exclusive access to content from our 1768 First Edition with your subscription. DiMaggio received the Most Valuable Player award for the American League in 1939, 1941, and 1947. He retired at the end of the 1951 season. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1955. In 1954 DiMaggio married film star Marilyn Monroe; this only added to his iconic status in American culture. Though this marriage lasted less than a year, the couple remained close until her death in 1962. In his retirement he acted as a spokesman for commercial concerns and worked for charitable causes. The lustre of his career remained undimmed at his death; he was loved by fans as much for his integrity and dignity as for his phenomenal playing skills. Joseph Paul DiMaggio[a] (November 25, 1914 – March 8, 1999), nicknamed “Joltin’ Joe” and “The Yankee Clipper”, was an American baseball center fielder who played his entire 13-year career in Major League Baseball for the New York Yankees. Born to Italian immigrants in California, he is widely considered one of the greatest baseball players of all time, and is perhaps best known for his 56-game hitting streak (May 15-July 16, 1941), a record that still stands. DiMaggio was a three-time Most Valuable Player Award winner and an All-Star in each of his 13 seasons. During his tenure with the Yankees, the club won ten American League pennants and nine World Series championships. His nine career World Series rings is second only to fellow Yankee Yogi Berra, who won ten. At the time of his retirement after the 1951 season, he ranked fifth in career home runs (361) and sixth in career slugging percentage. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1955 and was voted the sport’s greatest living player in a poll taken during the baseball’s centennial year of 1969. DiMaggio is widely known for his marriage and lifelong devotion to Marilyn Monroe. Parents as “enemy aliens”. He was named Paolo after his father Giuseppe’s favorite saint, Saint Paul. A baseball card of DiMaggio during his tenure with the San Francisco Seals, c. Giuseppe was a fisherman, as were generations of DiMaggios before him. According to statements from Joe’s brother Tom to biographer Maury Allen, Rosalia’s father wrote to her with the advice that Giuseppe could earn a better living in California than in their native Isola delle Femmine, a northwestern Sicilian village in the province of Palermo. After being processed on Ellis Island, Giuseppe worked his way across America, eventually settling near Rosalia’s father in Pittsburg, California, on the east side of the San Francisco Bay Area. Giuseppe hoped that his five sons would become fishermen. [4] DiMaggio recalled that he would do anything to get out of cleaning his father’s boat, as the smell of dead fish nauseated him. Giuseppe called him “lazy” and good-for-nothing. DiMaggio did not finish his education at Galileo High School and instead worked odd jobs including hawking newspapers, stacking boxes at a warehouse and working at an orange juice plant. DiMaggio was playing semi-pro ball when older brother Vince, playing for the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League (PCL), talked his manager into letting DiMaggio fill in at shortstop. Joe DiMaggio made his professional debut on October 1, 1932. From May 27 to July 25, 1933, he hit safely in 61 consecutive games, a PCL-record, [6] and second-longest in all of Minor League Baseball history. [7] “Baseball didn’t really get into my blood until I knocked off that hitting streak, ” he said. Getting a daily hit became more important to me than eating, drinking or sleeping. In 1934 DiMaggio suffered a career-threatening knee injury when he tore ligaments while stepping out of a jitney. Scout Bill Essick of the New York Yankees, convinced that the injury would heal, pestered his club to give him another look. He remained with the Seals for the 1935 season and batted. 398 with 154 runs batted in (RBIs) and 34 home runs. His team won the 1935 PCL title, and DiMaggio was named the league’s Most Valuable Player. Seven of the American League’s 1937 All-Star players: Lou Gehrig, Joe Cronin, Bill Dickey, Joe DiMaggio, Charlie Gehringer, Jimmie Foxx, and Hank Greenberg. All seven were inducted into the Hall of Fame. DiMaggio made his major league debut on May 3, 1936, batting ahead of Lou Gehrig in the lineup. The Yankees had not been to the World Series since 1932, but they won the next four Fall Classics. Over the course of his 13-year Major League career, DiMaggio led the Yankees to nine World Series championships, where he trails only Yogi Berra (10) in that category. DiMaggio set a franchise record for rookies in 1936 by hitting 29 home runs. DiMaggio accomplished the feat in 138 games. [10] His record stood for over 80 years until it was shattered by Aaron Judge, who tallied 52 homers in 2017. In 1939 DiMaggio was nicknamed the “Yankee Clipper” by Yankee’s stadium announcer Arch McDonald, when he likened DiMaggio’s speed and range in the outfield to the then-new Pan American airliner. DiMaggio was pictured with his son on the cover of the inaugural issue of SPORT magazine in September 1946. In 1947 Boston Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey and Yankees GM Larry MacPhail verbally agreed to trade DiMaggio for Ted Williams, but MacPhail refused to include Yogi Berra. In the September 1949 issue of SPORT, Hank Greenberg said that DiMaggio covered so much ground in center field that the only way to get a hit against the Yankees was to hit’em where Joe wasn’t. DiMaggio also stole home five times in his career. By 1950, he was ranked the second-best center fielder by the Sporting News, after Larry Doby. [15] After a poor 1951 season, various injuries, and a scouting report by the Brooklyn Dodgers that was turned over to the New York Giants and leaked to the press, DiMaggio announced his retirement at age 37 on December 11, 1951. [16] When remarking on his retirement to the Sporting News on December 19, 1951, he said. DiMaggio in 1951, his last year in baseball. I feel like I have reached the stage where I can no longer produce for my club, my manager, and my teammates. I had a poor year, but even if I had hit. 350, this would have been my last year. I was full of aches and pains and it had become a chore for me to play. When baseball is no longer fun, it’s no longer a game, and so, I’ve played my last game. Through May 2009, DiMaggio was tied with Mark McGwire for third place all-time in home runs over the first two calendar years in the major leagues (77), behind Phillies Hall of Famer Chuck Klein (83), and Milwaukee Brewers’ Ryan Braun (79). [17] Through 2011, he was one of seven major leaguers to have had at least four 30-homer, 100-RBI seasons in their first five years, along with Chuck Klein, Ted Williams, Ralph Kiner, Mark Teixeira, Albert Pujols, and Ryan Braun. [18] DiMaggio holds the record for most seasons with more home runs than strikeouts (minimum 20 home runs), a feat he accomplished seven times, and five times consecutively from 1937 to 1941. [19] DiMaggio could have possibly exceeded 500 home runs and 2,000 RBIs had he not served in the military during World War II, causing him to miss the 1943, 1944, and 1945 seasons. DiMaggio might have had better power-hitting statistics had his home park not been Yankee Stadium. As “The House That Ruth Built”, its nearby right field favored the Babe’s left-handed power. For right-handed hitters, its deep left and center fields made home runs almost impossible. Mickey Mantle recalled that he and Whitey Ford witnessed many DiMaggio blasts that would have been home runs anywhere other than Yankee Stadium (Ruth himself fell victim to that problem, as he also hit many long flyouts to center). Bill James calculated that DiMaggio lost more home runs due to his home park than any other player in history. Left-center field went as far back as 457 ft [139 m], where left-center rarely reaches 380 ft [116 m] in today’s ballparks. Al Gionfriddo’s famous catch in the 1947 World Series, which was close to the 415-foot mark [126 m] in left-center, would have been a home run in the Yankees’ current ballpark. DiMaggio hit 148 home runs in 3,360 at-bats at home versus 213 home runs in 3,461 at-bats on the road. His slugging percentage at home was. 546, and on the road, it was. Statistician Bill Jenkinson commented on these figures. DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle at Yankee Stadium in 1970, two years after Mantle’s retirement. For example, Joe DiMaggio was acutely handicapped by playing at Yankee Stadium. Every time he batted in his home field during his entire career, he did so knowing that it was physically impossible for him to hit a home run to the half of the field directly in front of him. If you look at a baseball field from foul line to foul line, it has a 90-degree radius. From the power alley in left-center field (430 in Joe’s time) to the fence in deep right center field (407 ft), it is 45-degrees. And Joe DiMaggio never hit a single home run over the fences at Yankee Stadium in that 45-degree graveyard. It was just too far. Joe was plenty strong; he routinely hit balls in the 425-foot range. But that just wasn’t good enough in cavernous Yankee Stadium. Like Ruth, he benefited from a few easy homers each season due to the short foul line distances. But he lost many more than he gained by constantly hitting long fly outs toward center field. Whereas most sluggers perform better on their home fields, DiMaggio hit only 41 percent of his career home runs in the Bronx. He hit 148 homers at Yankee Stadium. If he had hit the same exact pattern of batted balls with a typical modern stadium as his home, he would have belted about 225 homers during his home field career. DiMaggio became eligible for the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1953 but he was not elected until 1955. The Hall of Fame rules on the post-retirement induction waiting period had been revised in the interim, extending the waiting period from one to five years, but DiMaggio and Ted Lyons were exempted from the rule. DiMaggio told Baseball Digest in 1963 that the Brooklyn Dodgers had offered him their managerial job in 1953, but he turned it down. After being out of baseball since his retirement as a player, DiMaggio became the first hitting instructor of the newly relocated Oakland Athletics from 1968 to 1970. DiMaggio’s most famous achievement is his MLB record-breaking 56-game hitting streak in 1941. The streak began on May 15, a couple of weeks before the death of Lou Gehrig-who had been DiMaggio’s teammate from 1936 to 1939-when DiMaggio went one-for-four against Chicago White Sox pitcher Eddie Smith. [21] Major newspapers began to write about DiMaggio’s streak early on, but as he approached George Sisler’s modern era record of 41 games, it became a national phenomenon. Initially, DiMaggio showed little interest in breaking Sisler’s record, saying I’m not thinking a whole lot about it… I’ll either break it or I won’t. “[22] As he approached Sisler’s record, DiMaggio showed more interest, saying, “At the start I didn’t think much about it… [23] On June 29, 1941, DiMaggio doubled in the first game of a doubleheader against the Washington Senators at Griffith Stadium to tie Sisler’s record and then singled in the nightcap to extend his streak to 42. DiMaggio kisses his bat in 1941, the year he hit safely in 56 consecutive games. His wife Dorothy Arnold was pregnant with their son Joe Jr. While the streak was in progress. A Yankee Stadium crowd of 52,832 fans watched DiMaggio tie the all-time hitting streak record (44 games, Wee Willie Keeler in 1897) on July 1. [27] The next day against the Boston Red Sox, he homered into Yankee Stadium’s left field stands to extend his streak to 45, setting a new record. DiMaggio recorded 67 hits in 179 at-bats during the first 45 games of his streak, while Keeler recorded 88 hits in 201 at-bats. [28] DiMaggio continued hitting after breaking Keeler’s record, reaching 50 straight games on July 11 against the St. [29] On July 17 at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium, DiMaggio’s streak was finally snapped at 56 games, thanks in part to two backhand stops by Indians third baseman Ken Keltner. 408 during the streak with 15 home runs and 55 RBI. [31] The day after the streak ended, DiMaggio started another streak that lasted 16 games. The distinction of hitting safely in 72 of 73 games is worthy of mention. [32][33] The closest anyone has come to equaling DiMaggio is Pete Rose, who hit safely in 44 straight games in 1978. [34][35] During the streak, DiMaggio played in seven doubleheaders. The Yankees’ record during the streak was 41-13-2. DiMaggio’s streak is the most extraordinary thing that ever happened in American sports. Stephen Jay Gould[36]. Some consider DiMaggio’s streak a uniquely outstanding and unbreakable record and a statistical near-impossibility. Nobel Prize-winning physicist and sabermetrician Edward Mills Purcell calculated that, to have the likelihood of a hitting streak of 50 games occurring in the history of baseball up to the late 1980s be greater than 50%, fifty-two. 350 lifetime hitters would have to have existed instead of the actual three (Ty Cobb, Rogers Hornsby, and Shoeless Joe Jackson). His Harvard colleague Stephen Jay Gould, citing Purcell’s work, called DiMaggio’s 56-game achievement “the most extraordinary thing that ever happened in American sports”. [36] Samuel Arbesman and Steven Strogatz of Cornell University disagree. They conducted 10,000 computer simulations of Major League Baseball from 1871 to 2005, 42% of which produced streaks as long or longer, with record streaks ranging from 39 to 109 games and typical record streaks between 50 and 64 games. DiMaggio enlisted in the United States Army Air Forces on February 17, 1943, rising to the rank of sergeant. [37] He was released on a medical discharge in September 1945, due to chronic stomach ulcers. He spent most of his military career playing for baseball teams and in exhibition games against fellow Major Leaguers and minor league players, and superiors gave him special privileges due to his prewar fame. Embarrassed by his lifestyle, DiMaggio requested that he be given a combat assignment but was turned down. Giuseppe and Rosalia DiMaggio, both from Isola delle Femmine, were among the thousands of German, Japanese, and Italian immigrants classified as “enemy aliens” by the government after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Each was required to carry photo ID booklets at all times and were not allowed to travel outside a five-mile radius from their home without a permit. Giuseppe was barred from San Francisco Bay, where he had fished for decades, and his boat was seized. Rosalia became an American citizen in 1944, followed by Giuseppe in 1945. In January 1937, DiMaggio met actress Dorothy Arnold on the set of Manhattan Merry-Go-Round, in which he had a minor role, and she was an extra. They married at San Francisco’s St. Peter and Paul Church on November 19, 1939, as 20,000 well-wishers jammed the streets. Their son, Joseph Paul DiMaggio, Jr. [39] The couple divorced in 1944, while he was on leave from the Yankees during World War II. Monroe and DiMaggio when they were married in January 1954. According to her autobiography My Story, ghostwritten by Ben Hecht, [40] Marilyn Monroe originally did not want to meet DiMaggio, fearing that he was a stereotypical arrogant athlete. They eloped at San Francisco City Hall on January 14, 1954. Although she suffered from endometriosis, [41] Monroe and DiMaggio each expressed to reporters their desire to start a family. A violent fight between the couple occurred immediately after the skirt-blowing scene in The Seven Year Itch that was filmed on September 14, 1954, in front of Manhattan’s Trans-Lux 52nd Street Theater. [42] Then 20th Century Fox’s East Coast correspondent Bill Kobrin told the Palm Springs Desert Sun that it was director Billy Wilder’s idea to turn the shoot into a media circus. The couple then had a “yelling battle” in the theater lobby. [43] A month later, she contracted the services of celebrity attorney Jerry Giesler and filed for divorce on grounds of mental cruelty nine months after the wedding. [citation needed] After the failure of their marriage, DiMaggio underwent therapy, stopped drinking alcohol, and expanded his interests beyond baseball; he and Monroe read poetry together in their later years. On August 1, 1956, an International News wire photo of DiMaggio with Lee Meriwether gave rise to speculation that the couple were engaged, but Cramer wrote that it was a rumor started by Walter Winchell. Monroe biographer Donald Spoto claimed that DiMaggio was “very close to marrying” 1957 Miss America Marian McKnight, who won the crown with a Marilyn Monroe act, but McKnight denied it. [45] He was also linked to Liz Renay, Cleo Moore, Rita Gam, Marlene Dietrich, and Gloria DeHaven during this period and to Elizabeth Ray and Morgan Fairchild years later, but he never publicly confirmed any involvement with any woman. DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe staying at Imperial Hotel in Tokyo on their honeymoon. DiMaggio reentered Monroe’s life as her marriage to Arthur Miller was ending. On February 10, 1961, he secured her release from Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic in Manhattan. She joined him in Florida where he was a batting coach for the Yankees. Their “just friends” claim did not stop remarriage rumors from flying. Reporters staked out her Manhattan apartment building. Bob Hope “dedicated” Best Song nominee “The Second Time Around” to them at the 33rd Academy Awards. According to Maury Allen’s biography, DiMaggio was alarmed at how Monroe had fallen in with people he felt were detrimental to her well-being. She was found dead in her Brentwood, Los Angeles, home on August 5 after housekeeper Eunice Murray telephoned Monroe’s psychiatrist, Dr. [46] Her death was deemed a probable suicide by “Coroner to the Stars” Thomas Noguchi. It has also been the subject of conspiracy theories. Devastated, DiMaggio claimed her body and arranged for her funeral at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery; he barred Hollywood’s elite as well as members of the Kennedy family, including then-U. He had a half-dozen red roses delivered three times a week to her crypt for 20 years. [47] He refused to talk about her publicly or otherwise exploit their relationship. He never married again. According to DiMaggio’s attorney Morris Engelberg, DiMaggio’s last words were: I’ll finally get to see Marilyn. [48] However, Joe’s brother Dominic challenged both Engelberg’s version of Joe’s final moments as well as his motives. In the 1970s, DiMaggio became a spokesman for Mr. Coffee and would be the face of the electric drip coffee makers for over 20 years. Vincent Marotta, the CEO of North American Systems, which manufactured Mr. Coffee at the time, recruited DiMaggio for the advertising campaign. [51] DiMaggio’s spots proved successful with consumers. In a 2007 interview with The Columbus Dispatch, Marotta joked that millions of kids grew up thinking Joe DiMaggio was a famous appliance salesman. [51] Despite his commercials for Mr. Coffee, DiMaggio rarely drank coffee due to ulcers. [51] However, when he did drink coffee, DiMaggio preferred Sanka instant coffee rather than the coffee brewed by Mr. In 1972, DiMaggio became a spokesman for the Bowery Savings Bank. With the exception of a five-year hiatus in the 1980s, DiMaggio regularly made commercials for the financial institution until 1992. DiMaggio’s grave at Holy Cross Cemetery in Colma, California. DiMaggio, a heavy smoker for much of his adult life, [53] was admitted to Memorial Regional Hospital in Hollywood, Florida, on October 12, 1998, for lung cancer surgery and remained there for 99 days. DiMaggio’s funeral was held on March 11, 1999, at Sts. Peter and Paul Roman Catholic Church in San Francisco;[55] he was interred at Holy Cross Cemetery in Colma, California. DiMaggio’s son died that same year in August, at age 57. At his death, The New York Times called DiMaggio’s 1941 56-game hitting streak perhaps the most enduring record in sports. In an article in 1976 in Esquire magazine, sportswriter Harry Stein published an “All Time All-Star Argument Starter, ” consisting of five ethnic baseball teams. Joe DiMaggio was the center fielder on Stein’s Italian team. DiMaggio’s plaque at the Baseball Hall of Fame. On April 13, 1998, DiMaggio was given the Sports Legend Award at the 13th annual American Sportscasters Association Hall of Fame Awards Dinner in New York City. Henry Kissinger, former Secretary of State and a longtime fan of DiMaggio, made the presentation to the Yankee great. The event was one of DiMaggio’s last public appearances before taking ill. Yankee Stadium’s fifth monument was dedicated to DiMaggio on April 25, 1999, and the West Side Highway was officially renamed The Joe DiMaggio Highway in his honor. The Yankees wore DiMaggio’s number 5 on the left sleeves of their uniforms for the 1999 season. He is ranked No. 11 on The Sporting News’ list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players, and he was elected by fans to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team. In addition to his number 5 being retired by the New York Yankees, DiMaggio’s number was also retired by the Florida Marlins, who retired it in honor of their first team president, Carl Barger, who died five months before the team took the field for the first time in 1993. DiMaggio had been his favorite player. Joe DiMaggio’s number 5 was retired by the New York Yankees in 1952. On August 8, 2011, the United States Postal Service announced that an image of DiMaggio would appear on a stamp for the first time. It was issued as part of the “Major League Baseball All-Star Stamp Series, ” which came out in July 2012. According to American geneticist Mary-Claire King, in the spring of 1981 DiMaggio babysat her daughter at the San Francisco airport so King could drop her mother off to her flight to Chicago. According to King, if it were not for DiMaggio’s kindness, she would have almost certainly missed her own flight that was taking her and her daughter to Washington, D. A trip that eventually resulted in King’s getting her first major grant from the National Institutes of Health and the discovery of the breast and ovarian cancer-causing gene, BRCA1. DiMaggio insisted on being introduced as the “Greatest Living Ballplayer” at events, including Yankee Old-Timers Day. Billy Crystal was once punched in the stomach for not introducing him as such. DiMaggio played in 10 World Series, winning 9. His only loss was in the 1942 World Series. 271 (54-199), with 27 runs scored, 8 home runs and 30 RBI in 51 post-season games. President Ronald Reagan and DiMaggio at the White House, March 27, 1981, three days before the attempted assassination of Reagan. This article appears to contain trivial, minor, or unrelated references to popular culture. Please reorganize this content to explain the subject’s impact on popular culture, providing citations to reliable, secondary sources, rather than simply listing appearances. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. DiMaggio’s popularity during his career was such that he was referenced in film, television, literature, art, and music both during his career and decades after he retired. Pierre Bellocq: Canvas of Stars mural for Gallagher’s Steak House (2006)[60]. Robert Casilla: The Continuity of Greatness[61]. Devon Dikeou: Marilyn Monroe Wanted to be Buried in Pucci installation (2008)[62]. Bart Forbes: illustration of DiMaggio for the July 1999 Boys’ Life [65]. Zenos Frudakis: bronze sculpture of DiMaggio for the Joe DiMaggio Children’s Hospital[66]. Stephen Holland: Joe DiMaggio (2005). LeRoy Neiman: Joe DiMaggio, New York Yankees (1969), Joe DiMaggio, San Francisco Seals (1989), and The DiMaggio Cut (1998). Mark Ulriksen: illustration of DiMaggio for the cover of the April 12, 1999 The New Yorker. DC Comics’ 100 Bullets by Brian Azzarello and Eduardo Risso. “The Counterfifth Detective”, DiMaggio is recruited by Graves for the Minutemen[72]. “Idol Chatter”, the former baseball player befriended by Graves is based on DiMaggio[73]. DC Comics’ Sandman Mystery Theater Issue #1 (also collected in Sandman Mystery Theatre Book 1: The Tarantula, which contains issues 1-4). Harvey Comics’ Babe Ruth Sports Comics (August 1949)[74]. Parents’ Magazine’s True Comics #71 (May 1948)[75]. Revolutionary Comics’ Baseball Legends: Joe DiMaggio (July 1992)[76]. “Buck Wischnewski” is based on him in Alvah Bessie’s novel The Symbol. “The Athlete” is based on him in Joyce Carol Oates’s novel Blonde. The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway makes repeated references to “the great DiMaggio”. “The Silent Season of a Hero” by Gay Talese, is a celebrated 1966 piece for Esquire magazine. Tori Amos: “Father Lucifer” references DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe. Asia: “Joe DiMaggio’s Glove”[77]. Dan Bern: “Wasteland” references DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe. Billy Bragg and Woody Guthrie: “DiMaggio Done It Again”. Les Brown & His Band of Renown’s “Joltin’ Joe DiMaggio”[78]. Tim Curry: “I Do the Rock” references DiMaggio. Billy Joel: “We Didn’t Start The Fire”. Bon Jovi: “Captain Crash & the Beauty Queen From Mars” references DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe. Jennifer Lopez, featuring Nas: “I’m Gonna Be Alright” references DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe. Kinky Friedman: “Marilyn and Joe”. Demi Lovato: “Without the Love” references DiMaggio. Madonna: “Vogue” references DiMaggio. Man From Delmonte: “Beautiful People” references DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe. Rodgers and Hammerstein: “Bloody Mary” from South Pacific references DiMaggio. Abie Rotenberg: “The Great Joe DiMaggio’s Card”. Simon & Garfunkel: Mrs. Sleeper: “Romeo Me” references DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe. Vulfpeck: “1 for 1, Dimaggio”. Major Parkinson: “Solitary Home” references Dimaggio. 61, played by Michael Nouri. Diminished Capacity: a vendor at a baseball card show tries to sell cleat laces he claims were used by DiMaggio. Farewell, My Lovely: Marlowe follows DiMaggio’s hitting streak. The Goddess: “Dutch Seymour” is based on DiMaggio. Insignificance: “The Ballplayer” is based on DiMaggio. Murder in the First: Young follows DiMaggio’s hitting streak. Wonder Boys: James steals the jacket Marilyn Monroe wore the day she married DiMaggio from Gaskell, who is obsessed with the DiMaggio-Monroe marriage. A Bronx Tale: Robert De Niro’s character Lorenzo, tells his son why DiMaggio was the greatest ball player to ever live. Marilyn & Me, portrayed by Sal Landi. Marilyn: The Untold Story, portrayed by Frank Converse. Norma Jean & Marilyn, portrayed by Peter Dobson. The Rat Pack, portrayed by John Diehl. The Secret Life of Marilyn Monroe, portrayed by Jeffrey Dean Morgan. Insignificance (1982) by Terry Johnson: The Ballplayer is based on DiMaggio. Marilyn: An American Fable (1983): DiMaggio is a character. Arthur and Joe (2012) by Allan Havis: DiMaggio is a character[80]. Bronx Bombers (2013) by Eric Simonson: DiMaggio is a character[81]. The Bronx Is Burning, played by Christopher McDonald. Blonde, “The Baseball Player” is based on DiMaggio. The Carol Burnett Show: (Season 8, Episode 23), Harvey Korman plays DiMaggio in a mock Mr. The Flintstones: “Kleptomaniac Pebbles”, Fred tells Wilma that Bamm-Bamm “could be another Joe DiRockio”. Frasier: “Room Full of Heroes”, Martin dresses as DiMaggio, his boyhood hero. I Love Lucy: “Lucy is Enceinte”, Fred gives Lucy a baseball signed by DiMaggio. Mad Men: “Six Month Leave”, Hollis tells Peggy and Don that he is thinking of DiMaggio in the wake of Monroe’s death. MASH: “Pressure Points”, Potter references DiMaggio while talking to Freedman. Saturday Night Live: (Season 26, Episode 4), Jimmy Fallon as DiMaggio and Charlize Theron as Monroe. Second City Television: (Series 4, Cycle 3-9), Bill Murray plays DiMaggio in faux commercial “DiMaggio’s on the Wharf” with Eugene Levy as Dom DiMaggio, and Martin Short as Vince DiMaggio. Seinfeld: “The Note”, Kramer insists to Jerry, George, and Elaine that DiMaggio patronizes Dinky Donuts and dunks them in his coffee. Jerry doesn’t believe Kramer until the end when they all see DiMaggio do so. The Simpsons: “‘Tis the Fifteenth Season”, Mr. Burns gives Homer a DiMaggio rookie card. Smash: DiMaggio is a character in a Broadway musical about Marilyn Monroe. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine: “If Wishes Were Horses”, Sisko’s favorite player breaks DiMaggio’s hitting streak record[83].